Dear TWIMC [to whom it may concern],

Working we all are as things move instead of standing still. And with the motion time runs out and the desire to write and tell brings only frustration to those who do not wish to write the nearest personal thing to a form letter. But so many things are happening and being that I have come to that in the end, and here one may find it...

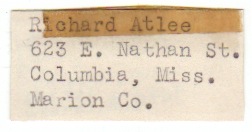

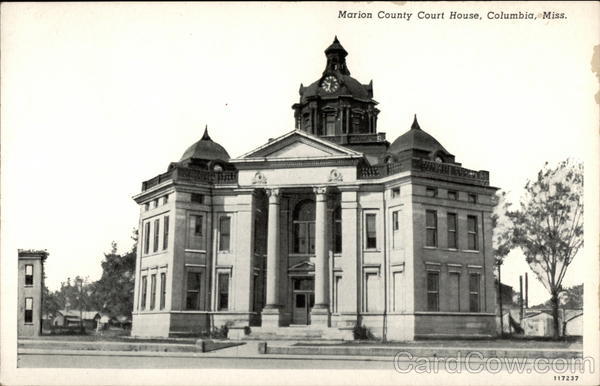

Thirty miles north of Bogaloosa (a little town, which nobody but the ingroup civil rights workers in southeast (fifth-district) Mississippi had ever heard of, up until a few months ago) is the county seat of Marion County. Marion County is a rectangular section of the Earth's surface holding about 24,000 souls of various racial mixtures perched precariously on the northeast corner of Louisiana.

There had been no civil rights activity in Marion County until this year (other than a pair of ethereal "government men" who apparently came through a while back straightening out registration errors). This year, the NAACP was supposed to set up a registration project. There is neither project nor office of the NAACP to be found in Colombia, the county seat.

There was much to be done, in spite of protestations that "we've been treating 'em right." The major industry in this, as in most of the counties in this area, is lumber and paper. Officially these plants and mills are unionized -- there is no evidence of a union in the county. In many places we go scale is subminimum (the worst area so far as pay goes is the maid's work: most work all day, generally getting meals, for an average of between $3 and $4 a day -- 25-30¢/hr. Discrimination in some aspect of work -- which jobs are obtainable, what conditions are to be worked under, how one is treated -- is from, all we can gather, universal. The park, the library, the city pool, most eating facilities, the movie, and even many bootleg operations are segregated. Out of over 6000 eligible Negroes (our exact figures were lost in an unfortunate incident this year to be described later), only 381 were registered as of last year. Earlier this year a federal injunction was passed down ordering the county registrar to remove the Constitution interpretation questions from the registration form, and since then, many have registered on their own. But the only thing Franklin Roosevelt considered worth fearing runs rampant here, and most Negroes haven't gone down to the courthouse.

Working in Biloxi last year, I met two men who were born and raised in and around Marion County: Curt Styles and Arthur Lee (Jake) Jacobs. I ran into them again this year in orientation in Hattiesburg, and they were interested in coming to Marion County, since the Fifth District is hurting as far as high-morale spirited projects go, and they were loyal to the Fifth District. The project would not at first be strictly official -- there was no allotment of people for MFDP [Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party] work in Marion County, but a group of us got together and decided to go anyway, so that it was not only the city of Columbia that was surprised when we turned up here. Two girls had come down after getting permission to do so -- neither had had any experience and had violated a number of security precautions, so after some behind-the-scenes action they did not return after the orientation and we went on to Laurel to work in the waiting period during which Curt was sounding out Marion County. Just as we had figured we were never going to get to Marion County we got the call from Curt, and tallyho off to the big war.

It has now been over three weeks since that Sunday evening when we stepped off the panel truck in Colombia and stared right into the faces of two rednecks passing by in a pickup, and began learning how fast news and rumors travel in a town of 7117 souls and lacks-of-soul.

I have no doubt that the whole town knew there were "freedom riders" somewhere in its viscera and was already beginning to retch. Curt had a warm welcome; the teenage community in the cafe we stepped into gave up with a surprisingly personal warmth; the cafe owner wasn't quite so enthusiastic -- someone had been beaten up outside and the cops arrived and there was the hunk of flesh (animal), clutching the angled down hunk of flesh (vegetable, non-herbaceous) [night-stick] and leaning forward intently for the capture, later coming in to buy a candy bar and stare hard at us.

The mayor had drastically cut the police force and added a couple of men, fresh from the cab company -- odd bunch, and after the few initial tickets, surprisingly one of the best physical allies we have here. Up until last Friday (10 days ago), the chief was a humorless man toward us, and then suddenly he began changing. And now we can kid around with just about everybody on the force including him -- just the other day, one of them helped us carve frankfurter roasting sticks (SPLURGE).

And we find that the mayor may be one of the most valuable all-around allies in the city -- he has met very often with us (particularly for the part-time job it is for him) and acted as a go-between on many occasions when we probably would have had to act blind and use direct action techniques to achieve ends. I can't help liking him, talking as he does about "our cause" (he doesn't get any particular part of the normal political advantage out of his job and apparently sincerely wishes just to get "his town" through the growing pains it must suffer, without worrying about reelection -- he is definitely not in an enviable position), and "those local darkies", sort of a contradiction in himself and in his relation to his environment.

So in the city we are OK, but outside the city limits it is the sheriff whose jurisdiction we are under, and the sheriff is a good old-fashioned redneck (southern diamond-backed rubber-neck) ("a little man who has got himself a big job and instead of being humbled in his lack of ability has taken advantage of it." -- Mayor McLean) with an even more bigoted chief deputy. We have to watch for him.

The FBI is cooperative -- I doubt very sympathetic, and I do not trust the representative by any means, though some in the group do.

In the rest of the town we have a cross-section of red-neck types; sincere, Bible-reading folks who believe we're beatnik troublemakers (the mayor did us a favor of telling everyone we weren't); members of the white business community, most of whom probably are ready to make the one step beyond knowing that a black dollar is as green as a white dollar; Negro Toms who make it possible for every plan (and some we've never even heard of) to be common knowledge all over the city in a matter of hours; and interested Negro people who sometimes are scared to even be seen with us, or scared to come to a meeting, but not to help us with some food or a steady hand and a hammer, and some (mostly teenagers) who have the intestinal fortitude and lack of responsibilities to come to meetings, singing freedom songs in the face of the generally present police, and sometimes take walks with us to places of perennial lily-whiteness -- nine of us (four white) go into the library and the mayor gets a call an hours later: 60 niggers just went in the library.

We have people. We have the time in history. We need a place. The town is absolutely typical: the business district is about three blocks long and less than two blocks wide: essentially a Christian cross with the courthouse at the join. The left crossbar contains the two banks, each owned by one of the Lampton brothers, and on the other side the major department store (two locations), owned by the Rankins.

|

|

|

| Columbia business district today |

Lampton Company today |

Main Street today |

| |

Photos courtesy of Rev. Bill McAtee |

Most of the rest of the town is also owned by the Rankins and Lamptons, and among them, the Walkers, the Cooks, and especially the fantastic number of Fortenberries, most of the business town is divided. (Two columns of Fortenberries in the phone book, two Drs. Fortenberry, one druggist Fortenberry, a barber Fortenberry, and the Mississippi textbook we got out of the library was co-authored by a Fortenberry (incidentally, the local FBI agent is also a Fortenberry).

The main street runs N-S. West of the business district is a white residential area, through which we generally have to walk on our almost daily jaunts into town from our house in the Negro section north of this area. South of the business district is another Negro area, and a half mile farther south is another one. It is only recently (in our first real registration drive) that we had hit the nearer of the northern areas ("crosstown") because of the lack of transportation (no car) and the risks inherent in walking through the white community. After the first week, however, we had a reasonable proportion of our meeting attendance originating in the other side of town.

|

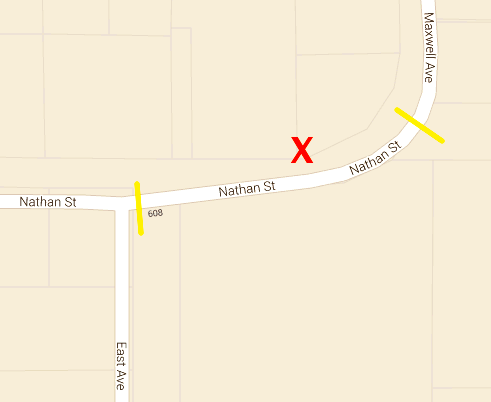

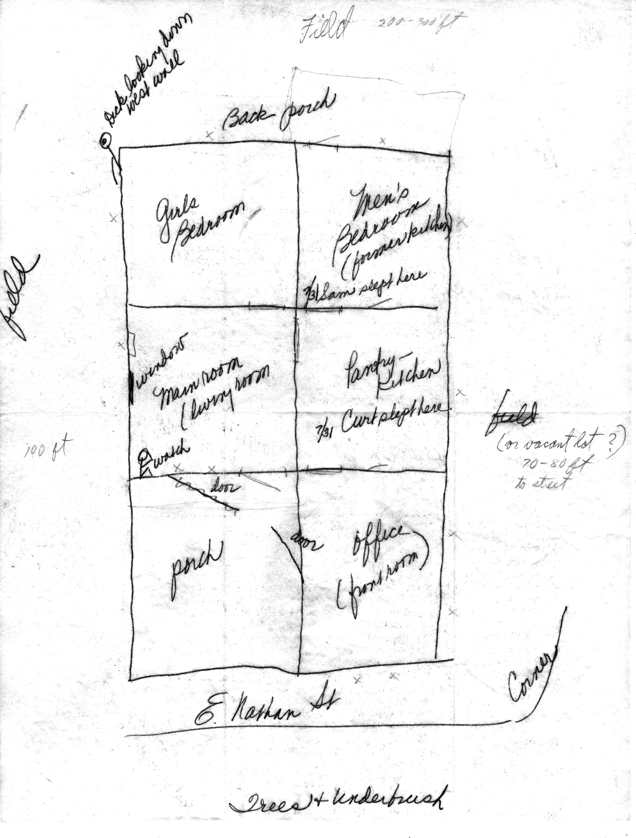

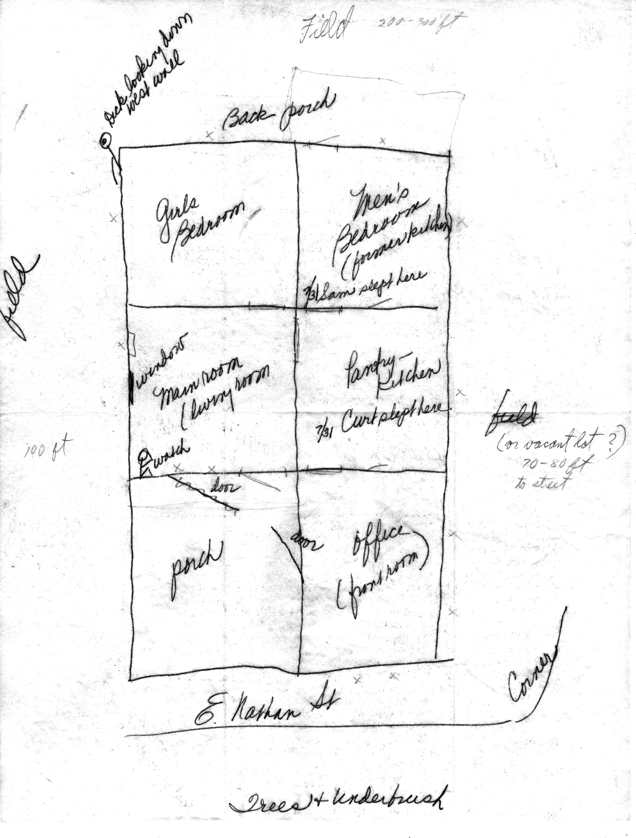

Our house (headquarters, Marion County and Columbia MFDP, housing one buck nigger, (Curt), one bastard (me), one Russian spy (Sam Gross), and two whores (Ann Marsh and Sara Schumer) is a one-story frame gray wood building located on a dirt road near a corner where everyone must slow down, causing us no end of heart stopping before our section of street was finally barricaded off by the police. Opposite it is a woods separating us from the white community, and on both sides of us and in back of us is a field (separating us on one side from a refreshment stand whose owner was a bit wary of us until he found out we were good business and boosted his business upwards of 200%; now he helps us out and lends us all manner of tools) -- the perfect place for a bombing, as Curt pointed out, even by "an amateur Klansman who has not even had a workshop."

The house is 2x3 rooms. The SE one is now an office, the NW one was converted to a porch, the E and W rooms a pantry and the main room, and the NE and NW rooms a bedroom (former kitchen) and another bedroom. We call them now respectively the office, a porch, the kitchen, the living room [referred to also as the meeting room], the men's bedroom and the girls' bedroom. We have a refrigerator without a latch, an electric stove, a table, a toilet table, a telephone table, a fireplace, and a falling apart simple chair. A food cabinet and three mattresses. And then.... |

|

Ann and one of the "beds"

|

Sara and the kitchen

|

Roadblocks (yellow bars in map above) to the west (with police car & officer, from porch) and east (from tree)

|

Porch, looking back along west side

|

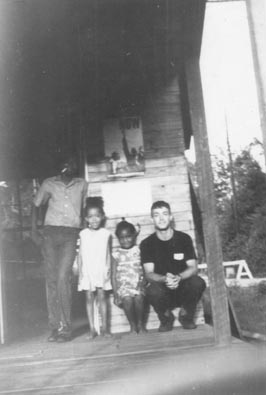

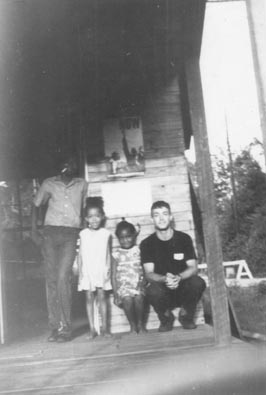

Kids and "Duck," against west wall of porch

|

(above photos by Dick Atlee)

|

People... things... specific miscellany... general etc.

|

The phone rings. We pick it up. Hello. Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. They hang up. We hang up.

The phone rings. We pick it up. Columbia FDP. They hang up. We hang up.

The phone rings. We....

The phone rings. I pick it up. A lady says, "Why you bastard." I say, "what, even the ladies?" She hangs up, I hang up...

We heard the library was segregated, and I went as a feeler. I asked several Negroes, several whites, and a policeman, and nobody could tell me where the library was. I went to the police station and they gave me an idea of the general direction. When I finally got there, two highway patrol cars and a police car were waiting for me. I went into the library and asked for a card. The librarian told me I would have to have a recommendation from the business community. So I went over to a shelf to get Mutiny On the Bounty for brief read-in.

It wasn't there, and as I looked up from the bottom shelf before which I was squatting, Jake Thompson (the town's favorite patrolman (usch)) and the highway man (!) were standing on either side. HP: well, Jake, what book are you looking for? Jake: I was looking for one called "how to live longer." I asked him if he'd ever read Mutiny, and he said no, he hadn't even been in the library in 20 years.

I found a science fiction book in the literature section of the one small wall of "adult non-fiction" and read it, wondering why people should have to fight to use a library like that...

The phone rings. It is a white lady. She says the only thing she doesn't like about integration is the idea of race-mixing. Sara points out that the whites have been doing most of that out of wedlock. She says she thinks anybody who does anything like that out of wedlock should be hung, but what is really worrying her is that it isn't fall and yet all the leaves are falling and God said this was what would happen at the end of the world...

Early in the game we walk into Penney's and for the once and only time a lady has the guts to come right out and ask us if we're civil rights workers (everyone here calls us freedom riders, and we take great pains to tell them that if we had a car it might make some sense, but we can't you see, we don't?)...

The phone rings. It is 10 p.m. They leave the phone off the hook for over 10 hours. We are without access to the police all night... [This happens more than once over the next weeks, and efforts to get the phone company to track such calls, even with intervention by parents with the Atlanta office, are fruitless.]

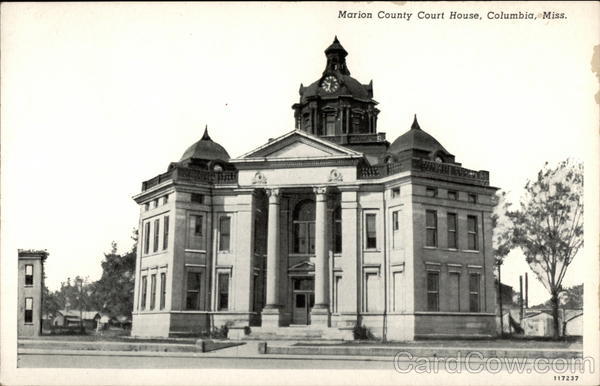

Sam sits in the courthouse, counting the people registering in our first "drive". He sits on a little seat next to a bubblegum machine. The janitor comes by and says get up. The janitor takes the seat and the bubblegum machine and puts them in the county superintendents office...

The Marion County Courthouse

The Marion County Courthouse

The old postcard may show it more like it was when we were there than it is today.

The phone rings. May I speak to Ann? Just a moment. Hello, this is Ann. Are you enjoying yourself. Yes. How much do you charge? I didn't come here to play, I came here to work. Well, enjoy yourself, it'll be your last night...

Sam moved to a shielded gas heater -- bent so you can see people have sat on it for the last 60 years. The deputy sheriff comes by. Move. Four men come with a long wrench, unscrew the gas connection, pick up the whole heater, and carried into the clerk's office... .

The phone rings. Is it true your mother had three puppies?...

No electricity. No windows. Constant zephyrs wafting either dust from the road or the extra sharp pigpen fragrance from the garbage in the back... And the animals who will take over the world after the next war. Ants. Drop a sugary spot, and it is less than ten minutes before it is covered with them. And they keep searching. I can feel him crawling on me now...

Late at night. On watch. The bedsprings on the back porch suddenly give a resounding rebound and there is a thump on the ground. What does a dynamite bomb sound like when it hits some bedsprings and bounces to the ground? Dead silence, keep listening, deep peering through the damnably difficult screening of the door. Whack, whack, pulse seems to be concentrated from your whole body in the big toe. No powder smell, no explosion. A rat?

The next night, a local cat and a couple of rats have it out on the porch and the cat loses. The next night, it is under the house, and no one will ever know the outcome of that battle. I haven't seen a cat since. Sara gets up from bed to check out some strange sounds and gets back to find new rat droppings on a sheet...

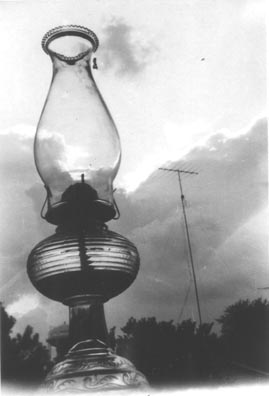

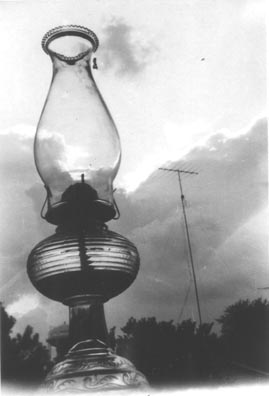

Sitting here at 10 p.m. typing this. Everyone has left and I am taking my turn watching the house while the rest are watching the prison escape movie I saw the first half of. The kerosene lamp lights up the window screen before me -- the geometry is lost in gray amorphism and I wonder who is out there in those woods across the street looking at me through this one-way shield if there is anybody and how do they feel toward me...

[One morning the kerosene lamp was found to have mysteriously exploded and burned during the night.]

[One morning the kerosene lamp was found to have mysteriously exploded and burned during the night.]

The phone rings. What did Martin Luther King say when his wife had twins. I don't know -- what? I've overcome. (??).

Originally, watches are planned for the meeting room. The observer sits in the SW corner bordering on the porch and peers around the window frame periodically or when a sound impresses itself upon dozing consciousness. If someone were to throw a bomb, the observer was to throw it away after running onto the porch (if there were obviously time) or preferably jump like hell into the pantry (now the kitchen) and continue a dive into the kitchen (now a bedroom) on the NE part of the building. It's better to not warn people since the main danger is the blast shock, and people might jump up and receive the full force if suddenly awakened.

We keep watch for a week and a half. After several vigorous discussions, we decided on Thursday of the second week to suspend watches because of the detriment it was obviously dealing out to our efficiency during the day.

Friday night [July 30] we had a meeting, the last guy (slightly drunk) didn't leave until 12. Everyone hit the sack, I stayed up to write a letter in the front office. At 12:30 a Negro guy came by slightly drunk; I told him the office was closed and he laughed. Several times cars came by and I turned out the light each time so that only the porch light was lit. (My clock was running fast, but I will give times by it.)

At about 1:15 there was a knock on the meeting room door. I fought with the hook latch on the front room door (both open on the porch). But by the time the door opened, whoever had knocked was gone.

At about 2:15 I finished and decided to knock off. I closed the light and undressed and then stepped forward to check the porch. I realized within a second that I had put my big toe down on a wasp. I opened the light and killed it more out of vengeance than inconvenience and sat on the floor grunting. Curt apparently woke up and thought I was announcing trouble, but not seeing any, he fell asleep. I got together and went out and there was nothing wrong, so I took my new travel alarm clock and went back to the former kitchen and lay down.

|

I recall that about two minutes later, I raised my head with the oddest feeling that something was going to happen, because I felt almost no surprise when I heard the thump on the porch. I could see fire immediately reflecting through the office door window and it came through the wall (I imagine by breaking glass in the door) and I rose up in a crouch and said "Hey! Fire. Fire!"

I heard everyone in motion almost at once, and I went into the pantry (now kitchen), where Curt was sleeping that night. I think I was just about standing up. I heard all these pops and thought they were firecrackers. I went back into the kitchen and saw Sam groveling on the floor just as Curt was doing. It began to dawn on me that this might be a good idea and I crammed down under the table next to the stove with Sam. Every time a "firecracker" went off, Sam would go "Oooh, oh oooh" and crunch further back under the stove, and I moved likewise, although I still think that at that point I knew what was going on, although there was shattering glass several times -- it sounded like Roman candles.

Meanwhile, Ann had gone through the window when I first spoke, and Sara was handing clothes out the window to her. When the first shots started Ann hit the ground immediately. Sara continued to take down clothes for a while -- there were bullets going through the wall within two feet of her, though we couldn't hear any sound of ripping wood or moving air -- I think the crackling of the fire drowned it out.

The shooting was in two sessions and then stopped. I crawled out from under the table and heard a car leaving around a curve to the east of the building. (Sam reports quite a bit of talking going on among us at this time (though neither Ann nor I remembers it.) The fire was completely filling the front room and the pantry was filled with smoke.

[Contacted in July, 2013, Sara Shumer recalled: "The only detail I may remember differently from the fire night is that I thought the last 3 shots came from the neighborhood and were shot into the air to let the whites know there was defensive fire."]

Curt suddenly remembered his clothes and ran back into the smoke. It will be a long time before the picture of the black top and bottom divided by white drawers and carrying a flag of clothing charged out of the smoke at us. We all hit the back porch, Sam dragging some of his stuff out (he came back and got it all later). Sam and I turned the hose on and I gave thumbs up on the hose end for pressure. Now I know why fire is seldom put out by a garden hose. I could not get more than halfway into the kitchen before the smoke was unbearable, and I couldn't see where to aim. Sam yelled at me until I realized he wanted me to fill a tub of water, which he dumped on the front porch. Water, water, less than everywhere, and all the boards sure shrank, but the change was chemical rather than physical. Then the hose stopped and until next morning I was sure someone had turned off our pressure (there was a kink somewhere).

The next clear memory I have (of the type which will stay for a long time) was standing at the NW corner of the building looking along the west side toward the road and seeing the fire roaring out of the porch, and thinking man, is this wild, what a really beautiful sight. It transfixed me until someone suggested we moved the salvaged clothes away in case everything went. So I grabbed a pile of loose clothes and someone started shooting again. I got down somewhat reluctantly (something like this is ridiculous went through my mind) in the only convenient position -- on my back. It felt even more ridiculous.

But here was a police car coming east on Nathan Street. It stopped and backed up around the corner and stopped, and at some point, a dark red something with a red flasher pulled up past the house. (Sara and I were the only ones who saw it and it was a mystery machine until many days later we realized it was the first fire truck.) Ann had been sent to the phone for police and fire departments, but she never made it. A lady nearby

[from this point on the typeface is different, and the subsequent pages were sent in a separate letter, leaving the readers in suspense]

had apparently already called them. But they and the police got there at the same time and it was within two minutes, as best we can figure it, of the beginning of our hot time in the old town.

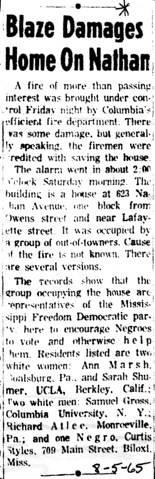

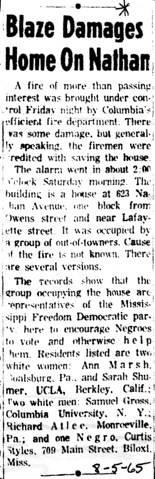

[Text for the articles at the right is available.]

|

|

Tupelo Journal, date unknown (saved clipping)

Hattiesburg American, July 31, 1965

Columbian-Progress, August 5, 1965

|

It seems rather strange. There is a volunteer fire department, and where I live, where there is a volunteer fire-department, many people have had to put out their own fires by the time the fire department arrives a half hour or hour later. Odd. But as it was, as I got up (there were only three shots) I noticed a surprisingly large number of people, both in the field with us and lined up over near the refreshment stand. It grew to be quite a crowd. There were firemen running with hoses and another fire truck had arrived (as we understand it, from another fire department (!)).

|

I began to realize that everything except my pajamas and one pair of socks was burning in that house, but I couldn't take it seriously, and when I found that my hat had been saved (my SNCC-type straw hat), I was overjoyed. Apparently we must have been in some kind of shock -- all we could do was joke around (later the Hattiesburg and Columbia papers broadly implied we had started the fire, and we understand the police have been spreading a rumor to the same effect -- perhaps the joking helped make this credible, I don't know). Then I realized my new clock was burnt and more laments until most of the fire was out. And I ran back across the field and found it only soaked and covered with ashes. It was unhurt, and I was so elated that I think it would have been a long time before I would have missed what I suspected was burnt (all my belongings save my shoes were in the front office).

|

|

SNCC-type hat

|

The flames had come strongly out of the window near the rear of the meeting room, and I'd seen fire or a clear reflection in the bedroom. The whole building would have gone up in less time than the less-than-less time it took the fire company to arrive, had it not been for about six or seven layers of linoleum on the floors of the office and the meeting room. The places on the walls where we had removed wallpaper were very badly charred -- I have no doubt the floors would have been useless but for the linoleum. Now that the linoleum is gone, if someone tries the same thing and the fire department gets here, oddly in the same time, we will have lost the house.

But we couldn't go back to get anything because the police had an investigation pending, so before we submitted to the request of the police chief that we go down to the station, we walked around the front of the building looking at the shattered and melted glass and the screens with over 20 holes in them. There were many more than this in all, and we found that the holes proceeded through one and sometimes two walls. The FBI picked up most of the lead, but we found around 10 pellets against the back wall the pantry and in the bedroom. The bullets in the pantry had gone through the wall at between chest and head level, and in the bedroom at about chest level. The fact that there was a pause between the time they threw the fire "bombs" and the time the shooting started (almost immediately after I called out) indicated very clearly that the intention was not merely to scare. There is no real reason whatsoever for no one having been hurt.

But we had to leave and go down for questioning. The police office is a one-room affair, and frigid with air-conditioning. They would only let one of us in at a time, and the rest had to sprawl against the walls of the station, perched in the middle of the road island on which it is located. Gradually the dawn came, cloudy at first, and with it cars and trucks, mostly white, many of whom came by more than once. The highway patrolman was asking the questions. When I said I had heard a car and thought I'd seen one, but wouldn't swear to having seen one, the chief interrupted to insist several times on my saying I couldn't swear to having seen it. And the interest in the case seemed to drop off immediately when they realized no one was hurt and they wouldn't have the Bogaloosa or Selma they had feared.

We had to wait an hour or two for the FBI to get here from Hattiesburg, of whom we finally ended up with three representatives. One briefly questioned Ann, Sara, and me, while another was still questioning Curt, and we finally had to interrupt Sam's griller a half hour after Curt was finished, so that Sam could get his mug shot at. But the FBI and the police couldn't find it in themselves to take us back, so we trudged back to the office (Curt and I barefoot) in rather hysterical spirits.

Only Jake Thompson was guarding the office. I suggested to everyone that we buck up with some of the fruitcake [snip] had sent down from Chicago. This was received with uproarious unanimity, and so I sneaked around the side and stomached myself up on the glassless window sill and opened the burned cabinet and sure enough the can was unburned. So while Sara got Jake over to the other side of the house. I trotted off down the road to a house of a friend and left it there safe.

It also being time for my next antibiotic pill (for the strep throat which had been bothering me for quite a while), I went up to Jake and told him I had some pills inside that the doctor had said were a matter of life and death, and he grudgingly went in the back door with me. The cabinet in which we kept what little food we had was against the back wall of the house. Everything in it was covered with soot and my heart sank when I saw the slightly melted plastic vial in which the pills had been. I pulled out the cotton and there they were -- undamaged: the first of many ironies we were to find that day.

We wandered around for about three hours and then the police and the FBI were finished with their investigation. Among other things, they had rifled our files in the bedroom and taken all our canvassing information and several affidavits against the police which we collected only a couple of days before.

Then the long process of shoveling out, cleaning up, and rebuilding began. My suitcase had been against the front wall of the front office, right next to the door through which the fire first burst. It looked like a cinder. And yet intact in it I found 15¢, many poems I brought with me for relaxation, some letters, most of my classical guitar book and transcription of German grammar, a wishbone, some handkerchiefs, socks, underwear, a Jews harp, and my harmonica (which looked so bad several local kids suggested I throw it out: an hour of cleaning and almost every reed works in tune).

In my toilet kit, which was in a cabinet, everything had been destroyed. I looked at the melted remains of the lens case in which I had kept my spare lenses and was just about to throw it out when I thought of the pills. I had to fight with it to get it opened, but inside were the lenses. When I try them out, they seemed perfectly OK. All the clothes (all dress clothes) in the cabinet had been completely destroyed -- in fact, the whole cabinet was gone. The rubble took almost a day to shovel out, but luck still looked upon us: a man from the country came by with a truck and in three trips (the many hours of hard labor it took to rebuild had begun) we got it all down to the city dump.

And then to relax. Night came, and I went up alone to the house to get something with our small electric lantern. In the vague light, it looked like a black skeleton, and inside with all the charcoal I became really afraid for the first time since I have been down here. A feeling which occasionally comes back on watch.

We slept in local houses that night, but there were threats the next day, and while we were able to get a house for the girls the next night, the three guys had to sleep in the corn patch a distance behind the house. From then on we slept in the house, barricading the windows with bedsprings and wood. The repairs have gone slowly. We knocked the front wall out of the office and knocked out the eaves and half of the porch and then the ceilings (sheet rock) of three of the rooms and all that was left of the screens. We got wood from a house which was being torn up and up went the wall and later the eaves and part of the porch roof and today the porch and hopefully tomorrow the last of the porch roof. And we screened the windows and with an ax and sling-scythe knocked down about a third of the woods across the street. And cleaned out the inside many times.

And during all this the mildew struck. And the ants. And the rats.

But though in the evenings -- after trying to pound nails in corners backhanded and left-handed and getting mouths and faces full of charcoal and finding that pounding a nail becomes a personal battle and getting angrier and angrier -- when I stop and relax, I find tremendous satisfaction in the work. I can see what I've accomplished, and barring unforeseen circumstances, it will not be undone. How different from the basic work we are here for. Which, by the way, is?

Because we work for the MFDP, we must consider ourselves at least nominally political organizers rather than civil rights workers. But we are a strange breed of organizers, because our party starts at the bottom rather than at the top. We can't come into an area with the county executive committee and precinct workers all prepared. Although the MFDP is open to all citizens, it is common knowledge that almost a complete majority of the membership is Negro, and hence we have a civil rights aspect, since the best organizing techniques we have are related to civil rights activity -- you can (that is, can -- success does not, as we have found out, follow immediately) organize the teen and college-age people with public accommodations testing (by organizing I mean to get people together, get them working with us, and get them thinking and talking on their own) and the adults through searching for new job opportunities and higher wages. And for everyone there, possible freedom schools, literacy classes, and ultimately political education classes. But in spite of the party we work for, we were (and still are in many parts of the Negro community as well as of the white community) the freedom riders.

God, the responsibility here is stunning -- I am overhearing a report from a lady that several kids are now in jail for alleged bicycle stealing, and maybe we can help. We aren't political organizers. We aren't civil rights workers. We aren't a legal institution, and we aren't a personal problem solving center, though some of the most difficult-to-relate-to people walk in and start beating our ears back with all sorts of problems. How far do you go toward accepting people -- like the lady with the crossed eyes who comes by trying to make out with Curt and borrow money off all of us and tie up everything, or the gentleman who came in here drunk one meeting night and lay down to go to sleep and managed to wet two of our three mattresses. Maybe some of us can define what we are. I'm not at all sure. Try samplings of what we have been doing, and perhaps decide yourself or selves.

There is one movie in this town (the other closed down a while back), with a local manager, but owned by a man living in Macomb. It was to be our first objective, as per the decision of the kids who packed the first meetings, to be approached on the Sunday a week after we hit town. But as Sunday rolled around, it became apparent the whole town had found out about it (we have cut down on some people we found out to be Uncle Toms and have let them know they are not welcome, but generally the correct story, along with (thank goodness), a large number of incorrect rumors, gets out long before we do). So we arbitrarily called it off so as to make it seem that the Uncle Tom stories were not to be trusted. But yet nobody showed up at Sunday to go anyway, even though they weren't supposed to know it had been called off -- you may draw your own conclusions, there being too many possible ones to say absolutely.

And so public accommodations disappeared from the scene until a week later, when the Monday [August 2] after charcoal Saturday, we hit the "public" library and the success there brought (the first day there were 5 local people) 7 local people to the library the second day and the decision Monday night to hit the movies.

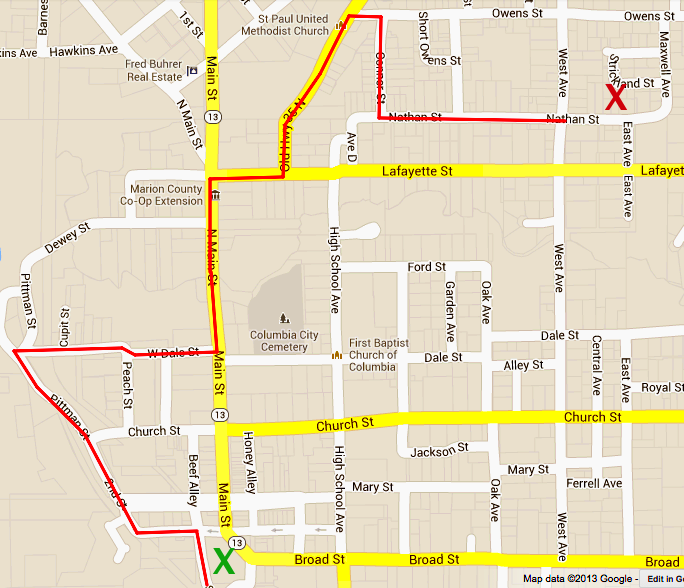

On Wednesday [August 4] we canvassed like hell to get people out, and after an anguishing wait, during which no one showed up, and after we had left with only three local people, we hadn't got a block down Nathan Street before we had a crowd of fifteen. After splitting into three groups at the end of Nathan Street, we proceeded through Charlie's [i.e., white] neighborhood by three entirely separate routes and timing was so perfect that we all hit the theater at the same time, running into a crowd of whites, the mayor, the police force, and the manager. And the manager said no and nothing else, so we went home triumphant and prepared to go again in a week.

The Marion Theater (desegregated 8/11&15) and Autry's Cafe (desegregated 8/21)

The Marion Theater (desegregated 8/11&15) and Autry's Cafe (desegregated 8/21)

(both empty at this later time; photo courtesy of Bill McAtee Society)

The mayor called up the owner, but the owner was on vacation, and called again Saturday and the owner's lawyer was on vacation, and suddenly on Monday [August 9] there was a meeting between the mayor and the owner and his lawyer and the owner agreed to desegregate if someone else desegregated first. The mayor suggested that we stop off at a restaurant on the way down. So that Wednesday [August 11] we went (only three local people showed -- a core who always stick with us) and were admitted. That is, everyone but me -- I stayed to watch the office that time, as someone always has to do since we still have no doors.

And at this point, we must look at some points of definition which we have bitterly come to see recently. To integrate means to make a facility available to people regardless of race, in which races are not arbitrarily kept separate, but come up hard against each other, to grind, grate, or slide as the case may be. The mayor does not want integration, though he honestly believes he does. The mayor wants desegregation, which means that some race formerly discriminated against is given access to a previously unavailable facility. When a real estate alliance pulls a scare and drives all the whites out of a block and replaces them with Negroes, this is a (admittedly far out version) form of desegregation . It ain't integration. When we go to a place, having warned the police, we get there to find the only whites are the owners, employees, and police.

This town is scared of a Selma or Bogaloosa -- the police spread rumors that we burned our house and that we are teaching local kids to steal bicycles from the whites, but they anxiously check all license numbers we give them, worry about crank calls, check us all through the night, and at all costs keep us away from white people. Not so much because they don't want integration as because they don't want an incident and all sorts of hard-core outsiders coming in.

And this must needs give us pause. In many a town there is an apathy until beatings and arrests begin (we heard from a white minister that the police force has been chastised for giving us those two initial parking tickets). Perhaps this was what we needed. But if there was to be an incident, there would have to be raw contact with whites, and the best time was the weekend, when the southern diamond-backed rubber-necks all came in from the country for a time on the town. And there could be no wall of police.

So for once we decided relatively independently of local people to try the movies last Sunday (15 August). The intention was to bring on an incident if there was to be ever an incident -- we were provoking it in the way some might strike a match to discover a gas leak. Curt and I did the main planning of it. And then came a trial (which I will eventually describe) and in desperation, immediately afterwards (this was the preceding Friday [August 13]) two desegregations of cafes (including first the one the mayor had asked us not to try because of the clientele) with about five minutes notice on the first and two minutes notice (that is, to the police) of the second.

If the mayor wondered at this, he should have been at the trial and seen why... but at any rate, we got a call from the mayor Saturday and he came over and talked to Curt and me. He didn't want any desegregation of public accommodations that weekend because according to him the whites were worked up about the violence in Chicago and Los Angeles ([Watts,] of which we knew next to nothing, owing to a lack of radio and newspaper -- though we see TV news at the sweet shop every now and then). And yet he had heard rumors that we were going to desegregate churches and everyone was up in arms. We had told him we would do no church desegregation because of the touchiness and our inexperience in the area of churches, and we simply reiterated our promise, but hedged around about other attempts and finally told him we would call him back.

(Again -- what power we have. That a mayor comes out -- doggedly assuring that we set all policy, in spite of what we tell him -- and must talk to us as equals in power, people who otherwise he would treat as kids interested in civil civic government. And a minister who invites us, and is scared of us though wanting to be friendly, and treats us in a way with the deference one might not normally get. Strange, this is...)

Curt and I had a long talk -- I was in charge of the operation since Curt would be out of town -- and we began to see the thing change significance and meaning before our very eyes. If we went ahead and lied and told them we wouldn't go and then went, his obvious faith in our honesty would be ended and we might lose him as a probably friendly contact in the white community. If we didn't go ahead, we would confuse (if they came) some 30 people who expressed interest in going. If we didn't call it off, we would have to let the mayor know we were going, and as he was head of the police force, we had no way of knowing what that would mean. But at times laying a hand on the line can show people for what they are, and we had little choice.

So I called him up (we lost two dimes -- twice he hung up before we could get the dime into the phone (around here you dial first and then put in the money), because he has been getting crank calls, just as we have -- finally we called him through the operator) and told him that we were planning to go to the movie on Sunday [August 15] for the purpose of finding out just how integrated the theater was -- whether we could go as individuals and without police protection, or whether the yielding and lack of violence only held for an open group of civil rights workers. And for this I mapped him a strategy.

The movie is on the east side of the courthouse square. The seats around the courthouse occupy the east, north and west sides, the two former generally occupied by whites, the latter by Negroes (no seats to the south). So we would go downtown in segregated groups of no more than three and converge on the west side of the courthouse from where we would send people one by one around the courthouse to the movie until all had been admitted or all rejected, in which case we would go around as a group and try to be admitted. The mayor told us the manager had been acting rather independent, and he wasn't sure we would be admitted in any case, in addition to which the manager had arbitrarily closed the theater several times in the past week (possibly on rumors). He said that the theater was closed often weekdays during school and nights when there were school football games, but not this arbitrarily. Several people in the Negro community told us this was not true, but even in the light of this he maintained his story. He promised us not to have obvious police protection or tell the manager this was coming.

But Sunday, he came by to check plans, and had old Jake Thompson (our favorite cop: the guy who gave us two tickets and from whom Curt had bummed a dime before he was known as a civil rights worker -- a not so old guy with sideburns and big motorcycle sunglasses) with him. So the police force now knew of it. So first we had an opening for the manager to find out -- the police are apparently willing to do anything to sabotage us.

Few people came, so I sent Robert Lee Hays (the embalmer, who has been our best -- and only -- local worker) down to get things started, with those who were here. I made a bad mistake of waiting to see if anyone would come in a bit late. The director of an operation should be on hand. So when no one came, I walked down to find several unexpected hitches.

First of all, the prices were different. The last two times they had been white 75¢ and Negroes 35¢ (Negroes in the balcony). This time (on a weekend) they were $1 and 25¢. Now the first one I can understand -- though I had not anticipated it, and hence the people who went didn't have enough money and walked back around the courthouse and returned again with enough money: clearly a suspicious procedure.

And Robert sent them in twos rather than as individuals. (As a result, we were not sure whether we were unknown at first, whether the mayor had told the manager, or the police had told the manager. And if we were known, our experiment was a failure.)

However, lowering the Negro prices on the weekend has some very interesting overtones in terms of reaction to civil rights pressure. At any rate, Robert and I were the last to go in and we had only $1.80 between us (it is indeed interesting sitting here in the front office typing. I just had to call the police because several times. I've seen flashes of light in the woods across the road...). So I went upstairs to the Negro section. Physically it isn't bad, though I hear the seats are much older than the ones downstairs; the only objection I could make to it is moral.

But when we came out, there was no white crowd as there had been last time. And Jake Thompson, complete with shades and sideburns, but in a sport shirt, had been in the movie. If anyone in town didn't know who he was, they should have been running the State Association For The Blind refreshment stand in the courthouse. So Sunday itself was a miscalculation: we will have to go Saturday if we want any kind of confrontation.

And as a result, Sunday was essentially a lost attempt -- it showed us nothing concrete except that we were again permitted to sit in the "wrong" sections of the movie. This happens all the time in less distinct ways: something relatively clear and with a pretty straightforward purpose becomes translated and perverted through a series of changes until it is not recognizable (like a rumor or a bill in Congress).

(August 21) Today for the first time we really hit the town in the classical place to hit a white southerner -- his pocketbook. This is not to say we were successful, but we tried, and undoubtedly left some impression. Such as maybe we are serious. This was the first of hopefully many days of picket-boycotting of the store, which we believe falsely accused two daughters of a family which is our biggest participation source (where there are 11 grown kids from about 25 on down).

Briefly, the two girls were walking to town and had decided to return since one of the girls decided she hadn't dressed properly for the occasion, when the police drove by with the manager of the store, stopped them, searched their pocketbooks, and went on. Later they passed again, this time, apparently without the store manager, and stopped and tried to verbally force the girls into the car. They refused until a Coca-Cola man came across the street (it was apparently quite a scene with a large crowd gathered) and shoved them both into the car. This was quite a mystery -- during the trial (which I want to relate later) the police denied he existed. But he appeared today, as shall become apparent forthwith (meanforth, therewhile, hencewith, or something like this).

The trial was conducted with really gross injustice (not Sam's type) and the resulting fines (conviction was on very dubious identification) forced one of the girls to drop her plans to go to college and just about broke our project (we had to lend them enough money to pay the fines off). It was this trial, the anger it aroused, and the location of many people all in one place, that led to two cafe integrations (or least desegregations), performed immediately after the trial, with almost no notice given the police -- we were all fighting mad and disgusted. And last night, in a meeting which Sara and I missed because we were attending an evening of a revival to mention our forthcoming trip to Washington, a new birth of morale was born as a result of that trial.

About two weeks ago I met a senior from Jackson State College whose home is around the corner. He said he would have to go back to school for a week, but after that he could help us in any way possible. He got back for Wednesday's meeting and in his enthusiasm (either strength of character or innocence of the situation) we found new hope.

Monday's [August 16] meeting, with Curt gone in New York and Detroit, was a disaster of trying to suggest aspects of organizing and drawing complete blanks. We have begun to see the end of the summer creeping in our general direction, and still we have no last will and testament of organization to leave behind us, through which the people can operate and make this hole a decent place for them to live. This was our purpose and Monday night, it became very apparent that we were failing.

After much recrimination and a long session of discouraging analysis we let things ride, and Wednesday [August 18], the guy from around the corner came and showed himself to be a real live wire. And Friday [August 20] (meeting every MWF about 8PM), he and a freedom-high girl from Prentiss (about 30 miles north in Jefferson Davis County) came and I understand it was a wildly successful meeting in which it was decided to boycott the Sunflower grocery store (the main supermarket in town -- the one which accused the girls of shoplifting, and sadly the only source of large economy sizes, molasses, and wheat germ). There were still people there singing an hour after the meeting had closed, when we arrived.

The Sunflower grocery store -- in a newer incarnation

The Sunflower grocery store -- in a newer incarnation

(photo courtesy Rev. Bill McAtee, slightly enhanced)

We got to sleep at 12:30, I took two hours of watch, and we woke up at seven o'clock. (God, was it terrible getting out of bed that early since we rarely make it before 9:00, but what a beautiful experience -- I'd forgotten the pleasure of washing your face outside under a new sky in the fresh morning washed all during the previous night.) By 9:00 everybody but the guy around the corner was ready -- his mother had made him afraid for her the night before -- he is smart, enthusiastic, and I think has the guts to do anything with us, but it is always the parents...

The family that helps us so much has a father who is independent of the whites and loves truth: he refused to let the girls plead guilty to get off with a minimum fine. And 12 of us hopped into the family's pickup under threatening skies in tremendous spirits and hit the road, snuck up behind the town and pulled around the corner of the store before anyone could have seen and reported us. I jumped out and went into a neighboring 5&10 and got poster board and a black marker (already having my trusty blue, purple, red, yellow, and green ones) and some waterproof plastic spray, while the group went in to demand an apology, a refund of all fines, and the hiring of a Negro clerk, all of which we felt under the circumstances were reasonable. Naturally the store did not think so, and with a brief flourishing of marking pens, we had signs and were marching...

|

There are picket captains at each end of the line. The sidewalk is too narrow and one half of the ring walks in the gutter. Old Chief Johnson blusters up and says "Are you going to move out into the street?" "Is there any reason for that, sir?" "All I ask you is whether you are going to get out into that street!" "Will you guarantee us that no one will come around this corner and run us down?" "I don't guarantee you anything!!" We didn't move. He went away. The mayor comes and politely asks us to avoid blocking the entrance, which we do.

The crowd of crackers, pecker-woods, middle-class whites, and curious Negroes begins to form. Were I a decent white southerner, the crowd of thugs and hoods standing there would have frightened the wits out of me. The police are out in force -- they arrived while I was in the 5&10. The whites start forming crowds in the first row of the parking lot directly opposite the store -- there are many of them, for it is Saturday and the whole county comes to town -- precisely why we chose Saturday.

The signs entreat people not to buy in the store... A lady shouts at the top of her voice they sure are doing great business in there now, almost sold out, keep up the good work...

A man and the chief stand before me as I turn: That one with a smile must be named cock. Yeah, you can tell by the smile his name is cock. The chief says, I'd like to knock his head off...

The first break in tension comes. A man is violently belaboring the poor mayor, insisting that the boy in the red shoes (the hallmark of the members of the big family) must be a communist.

A few minutes later a car peels out of the curb and runs us off onto the sidewalk. The tension returns...

A man is whittling with a jackknife. He is the same man who was holding a jackknife open in plain view in the front row of seats during the trial, holding it as if it were part of his anatomy...

A lady says, if I were a white girl I would be ashamed... The white men aren't. One walks up to Ann and asks her price. Ann says please refer all questions to the picket captain...

I notice a commotion in front of me. This man is not so polite. He has just approached one of the girls who was arrested, and in one motion kicked her in the leg near the groin and shoved her off the sidewalk. As he knocks me off the sidewalk on his way back along the line, I see Sam come fuming past. We grab him and turn him around -- he only wanted to take the guy's picture. It is the mysterious Coca-Cola man. As the cops clear the whites from near the door we see them talking in a friendly fashion to one of the cops who has been friendliest to us.

|

Tonight, the girl has a bad bruise on the inside of her thigh, and a pins-and-needles feeling in her lower leg, in addition to a low level of general leg pain. She's lucky he didn't get his foot high enough. They say it is not a man you should hate, but if you hate anything at all, hate his ways. Is this not difficult occasionally? DAMN HIM!!! He had knocked Sam off the walk and would have got Ann somehow but for the fact that she managed to duck...

Every now and then I see a certain type of man -- he always has a straw hat and intense light blue eyes. The same eyes, only at first empty, I had seen the first day I worked in the Chicago state mental hospital. I stared two of them down (one left during a circuit), hating their type worse and worse with each one. Then I noticed that someone I was working on was opening a store door for overburdened ladies.... Hate their ways, not them. I stop trying to stare him down and we let each other alone...

And we left in shifts of two and three to eat at the cafe we integrated with the movie. The lady insisted we sit at one particular table, she took an endless time to serve us, served about 3 oz of Coke in a glass of ice for 10¢, and for those order hamburgers, they were inedible, because there was so much pepper on them. That place is not integrated. I wonder what it is?...

In a way we were looking for trouble. Aside from the attack and the legs of lead from 5 hours of walking we had none. We left at 2:30. I went back at 5 to telegraph some money to Jake in Jackson. I think it will be a long time before we can again walk the streets without fear. Or meet the same courtesy from merchants. The follow-up will be difficult to organize, but perhaps...

They say in Marion County.

That freedom's on the rise.

Those whitefolks, they ain't got a chance

Unless they organize...

-- which side are you on?

|

|

The white man says.

He'll cut you down to size.

We got to get him first

So let's organize...

-- keep your eyes on the prize

|

If we can do it, it is a matter of time, who gets to organization the fustest with the mostest: a man comes up during the picket and slaps a sign on the store window. Help beat CORE. Buy from picketed merchants. A matter of time perhaps.

But in some ways, we and the chief think alike. I remember the thoughts before the police barricaded the road. This morning, the chief came over to some cars who were passing excessively slowly and said, 25¢ a look, a dollar a stop...

The day we first integrated -- excuse me, desegregated -- a cafe, the owner called up very bitterly and told us if we really wanted to do the job we shouldn't pick on the little man like him. Why not get the big people who are responsible: the Rankins and the Lamptons. And tonight we got an anonymous call to the same effect...

Tonight we were again scheduled to look for trouble -- to really see what an integration attempt in this town would bring: to go to the place the mayor warned us away from, and to go on Saturday night. But it doesn't look like the people we were hoping for will come, so we may not go.

When am I afraid? When among all the nervousness and scares is the time when we are afraid? Last year in Biloxi, I realized an important definition: courage is the inability to identify oneself with real dangers. It won't happen to me. One of our Negro staff members is going to the county in Alabama where the Episcopal student was killed and the priest badly hurt. He called us up and we discovered he felt uncomfortable about the idea of our going to this cafe Saturday night. Strange...

It looks like our people are here, in the middle of this unbelievable downpour (the main street in this area is for a whole block under about 3-4 inches of water).

(Since it looks like we will be going, I'll talk about the weather -- what else -- till then, and then let you know how it goes. It has been raining almost every day now for about a week. There have been a couple of comfortable days here below 85, and we were blessed during our rebuilding with hot but for several days non-humid weather. But generally it is about 90 with very high humidity, and at least for me, to stop means to leave a puddle. The sun burns down only in the early morning, but it boils down during the rest of the day. And shirts are changed and changed and changed and the only relief is a freshly wetted shirt straight from a hose, and in the general stillness of the air even it is little help. I can't write on such days without a blocking paper to keep my hand from sticking to the paper and getting the paper oily enough that even a fountain pen has difficulty on it, much less a simple write-on-butter ballpoint pen.

But the nights. The nights are all the same, regardless of rain or the amazing display of stars so frequently appearing here (though in summer to see one -- and with a drop of the head two, and with even more bowing all three -- of the points of Orion's belt hanging from the kitchen window top was a magical experience I won't forget). "Deep into the darkness peering, long I stood there, wondering, fearing..." Now we know what it is to peer deep into the darkness, to strain the eyes even beyond their vitamin A packed capabilities. To hear a sudden sound and feel the panic as it always was, suppressed as it might be.

[I found that the only way I could keep myself awake on watch was to chew on caraway seeds, one at a time. The bitterness was probably better than caffeine. I doubt it was what my friends in Chicago had in mind when they mailed me a packet of the seeds.]

OK, we go...)

Man, quite an evening that was. To put it succinctly. With the rain beginning to become a pour again, we piled six people into a Falcon convertible owned by Hezekiah (Hezzy, who I promised to write if I ever found someone with his name) Allamafallabuster (that last name has been slightly altered for anonymity), who has been a cheerful face and participant for quite a while -- a fast but good guy -- and four people into the truck, and pulled out, again with morale soaring. We planned for the truck (which is known) to park near the cafe (Autry's Cafe), while the car (which is unknown) would go around the courthouse and let us out and then be waiting for us -- Hezzy was afraid he'd get sick from nervousness, though I doubt he is really the sort of guy for that, and I think I was born out a bit later.

We drove around the courthouse twice before we decided the place to disembark and finally settled on the dark south side. With plans still not quite certain (except that Ann would stay between Sam and me to avoid the past accusation that one of the Negroes was holding Sara's hand -- Sara was at this point back at the office), we exploded slowly from the car and headed around the courthouse past the dark and deserted truck -- they were supposed to have waited for us -- and over to a point across the street from the cafe. So we went in without them. A couple of the guys had gone down a half-hour before to case the joint and said it was about half-filled with rednecks and local high-school type hoods, just like one would find in a Northern town. When we looked over, there were only about two people outside and three people inside. The five of us went inside and went to the back and next booth for safety. I was in front, and when I looked around, all nine of us were there. Lord knows where the others of been hiding, but they did a tremendous job.

We all sat down and I went up front, where already there were about five more people now, and called up the police and told them we had an integrated group in Autry's and the guy said oh and do you want to speak to Chief Johnson and I said yes I guess so and Chief Johnson said hello (o-god-not-again type hello) and I said hello Chief Johnson there is an integrated group in Autry's and I thought you should know and he said yes and I said goodbye. He and Smiley (the friendly heavy set cop) came by and wandered around until we were through. (Mrs. Autry, apparently a very nice person, kept telling us over and over again. "You had better call the police. Those people out there -- I know them. They don't give 10¢ for your lives.")

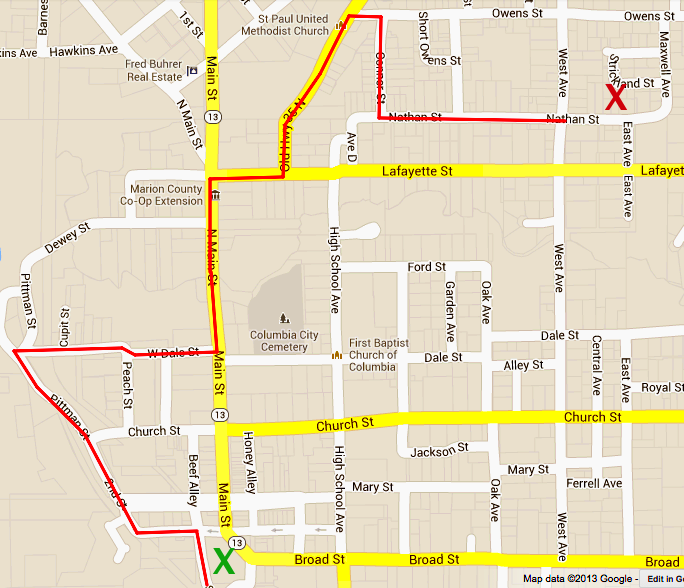

When we left, it was in approximately the same order. As I got to the pinball machine three local hoods stopped playing and walked past me brushing but... nothing. I had thought that aha, this was it, but it wasn't, and we walked out past about twenty-five people by now and the police were ignoring us, so hustle fast through the dark rain. Man that was a hustle. I looked behind and people were catching up and I looked to the left to see the truck riders really running to get back to the truck. Bundle into the car fast and look around for the sixth rider -- Sam said he'd gone to the truck. But we had to circle the courthouse to check. The police followed us to the car, but in the highly complex maneuver of driving around a courthouse we lost them. No rider. So out a back alley to Second Street, left into the long winding dirt road heading for Smith quarter.

Out about a quarter mile, we noticed a car was following us, and it wasn't a police car. So Hezzy, who was afraid of nervousness, leaned casually on his window and, driving with 1-1/2 hands, said, "When someone starts chasing me, I just sort of -crunch- shift into -roar- second." Forty. Fifty. Puddles spraying up on all sides and corners slipping by badly. The car was still behind us -- we had all scrunched down in the back seat in town to keep the group apparently segregated and none of us had bothered to come up for air except to look. Lead onto Dale Street, left on Highway 13, right through the right-after-stop red light. Yep, they were following us, so instead of turning onto Nathan Street, Hezzy turned a block early onto Highway 35 and I thought, o brother, we'll end up in the stix when they finally catch us. And it sure looked like they were going to -- when they came around that corner, they must've gotten into passing gear, because the headlights speeded up and became visibly growing. I didn't know where we were as Hezzy turned right onto Owen Street and immediately right again on Connor, a dirt street. And we lost them.

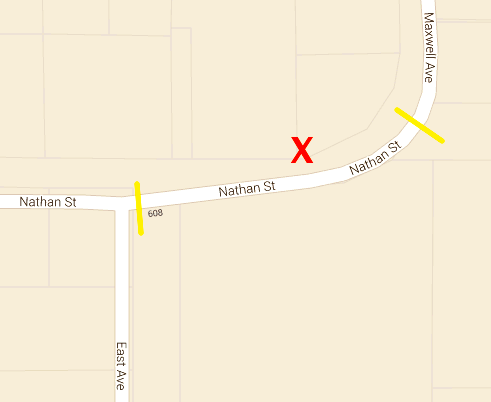

My best attempt at reconstructing this chase from the above description

My best attempt at reconstructing this chase from the above description

So a speedy ride up Nathan brought us back and we all jumped out and ran up to the house -- the truck was already there -- and after a brief consultation everyone except the four of us left and hit the road. It was an interesting night, all right, with double watches and tension, but I fell asleep halfway through my watch, so it was lucky I was watching with someone else up....

I will stop here and mail these since Ann is constantly pecking away to use the typewriter and I am running out of steam. The wait to write up the trial was kind of long and I am losing enthusiasm on that subject, so we'll just wait a bit longer....

Come listen to our telephone

Hear the white folks for a spell:

They'll cuss and swear till your ears curl up

And you go into a nonviolent shell.

-- which side are you on?

|