Letters from Mississippi -- The People

(people mentioned in -- and linked from -- the letters)

Updated: 23 September 2013

(

Home <

Issues <

Mississippi letters

)

Printable PDF

|

There are many people mentioned in these letters, and others that arose in the development of this site -- some well-known, most not. I have searched for further information on them, and where I could find such, I've linked those names to this page. I'd originally linked them to the original sources, but sometimes the information relevant to the person was buried in multi-page documents or graphics of newspaper pages. So I've extracted that information, and provided a link to the original sources. My own comments are in italics. Caveat: In some cases what I've presented is all I could find, in other cases I just chose enough to give a relevant context, and some of the snippets of information are more informative than others.

The Players

|

Louis Ashley

|

||||||||

|

Barry Clemson

Here's his "short bio." For an extended, fascinating description of his Mississippi experience, see his site. I started an academic journey that took me through separate degrees in science, politics, and management. As all these fields might suggest, I had some trouble deciding what I wanted to be when I grew up In 1964, in the middle of my undergraduate work, I joined almost a thousand other Northern students as part of the Mississippi Freedom Summer assault on the segregated South. I stayed in Mississippi until April of 1965 and during that time was attacked by both civilians and a policeman, was threatened by a couple of mobs and by a man with a rifle, and was arrested. God must have been watching me pretty closely, because although I thought I was about to be killed several times, I was never even injured. My "career" has taken me through a dizzying array of different roles including custom manufacturing, community development, university teaching & research, software development, carpentry, and (since retirement in 2006) writing, both fiction and essays. For a long time, this odyssey through all these careers puzzled me, but I recently realized that all of it was God's way of preparing me for writing fiction which explores the uses of strategic nonviolence. |

||||||||

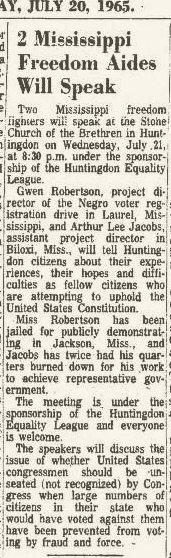

Rev. Nathan Andrew Dickson

When we arrived in Columbia, we didn't realize that that very day N.A. and Bill had, with the mayor's approval, mailed a much-worked-over letter to key people in their congregations. Partly in reaction to the failure of the county school board to submit a desegregation plan to the federal government, the letter's "For Your Consideration" lined out the need to begin to take positive action in the face of inevitable forces of change that were coming one way or the other, forces which could and would make or break the town. We didn't realize that the mayor and the Six were laying plans for meetings of white and black community leaders and for the eventual creation of a biracial town steering committee. In short, we didn't realize how lucky we were that all this groundwork had been laid. We naively tended to attribute our survival solely to the mayor's strong leadership qualities. |

||||||||

|

Margaret Dobbins

Margaret Dobbins, a college student from Ohio, also went to Mississippi that summer. Dobbins subsequently came to study at the University of Pittsburgh, where she met her future husband, Jake Milliones, and dedicated herself so completely to the educational uplift of black pupils that a school was named in her memory. -- The Civil Rights Movement in Pittsburgh: To Make This City "Some Place Special," Laurence Glasco, p.7-8 |

||||||||

Jim Draper

Draper concluded his newspaper career and worked with the Justice Department's community relations service in Memphis, "trying to keep people from killing each other" during Civil Rights marches. -- Jim Draper, an activist to the end, Corvallis (OR) Gazette Times, May 14, 2004 obituary |

||||||||

|

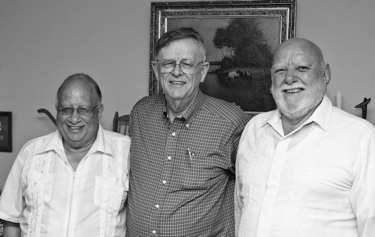

Dwain Epps (picture: see Rev. Bill McAtee)

Rev. Bill McAtee was coming to the end of the usual five-year "call" as pastor at the Amory (MS) Presbyterian Church, and was considering staying, having arranged for a summer sabbatical to finish a master's thesis he'd been working on. However, his life was to suddenly change direction with a visit from the pastoral search committee from the Columbia (MS) Presbyterian Church. They eventually prevailed upon him to come to Columbia, and arranged for him to have that sabbatical, getting a seminary student they knew at San Francisco Presbyterian Seminary, Dwain Epps, an "obvious Yankee" with civil rights sympathies, to fill in as a substitute preacher. He made contact with COFO before arriving, and tried to keep in touch that summer to know what he might have to expect in Columbia. Epps and Rev. McAtee began building "deep and long-lasting relationship" during a long June drive to and from the wedding of a mutual friend, which gave them a lot of time to discuss social issues. During that summer, Epps was watched by the White Citizens Council, but developed a strong relationship with the like-minded Methodist minister, N.A. Dickson, meeting "out in the woods" to discuss what was happening. Epps also made strong connections with young people in the church, and spoke carefully about race relations. Unbeknownst to him, though -- and to Rev. McAtee, until after he returned -- the church's Session (elders) had adopted in June a resolution that blacks were to be turned away if they showed up for services. The moment of truth to test this, however, never came, for better or worse. Epps became a Presbyterian minister three years later, and worked in various countries and with the World Council of Churches liaison at the U.N., retiring in 2002 to a village in Switzerland. In commenting on the continuing "attitude of mutual [racial] distrust," he said, "Until it all comes out, in a spirit of humility, acknowledgment of complicity, and respect for others who were as caught up in contradiction as we were, how are we to build the ground for that better future," and noting that hatred has a long memory. |

||||||||

|

Joy Falk

Call Slumlord Records Up, Council Urged. Mrs. Joy Falk, of the Clearing House for Open Occupancy Selection (CHOOSE), called for "stronger measures" to enforce fair housing practices in all sections. "It has become impossible for Negro families to find decent housing in the $80 to $90 a month range," she said. -- Pittsburgh Post Gazette, September 29, 1966 |

||||||||

|

Dr. Leslie Falk

Leslie A. Falk, born on April 19, 1915, was reared in St. Louis, Missouri. By 1936, he graduated from the University of Illinois, entered Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and applied for a Rhodes Scholarship. From 1937 to 1940, the Rhodes Scholarship enabled him to attend Oxford University, work with Sir Howard Florey (and other scientists) in the development of a method for the extraction of penicillin from mold, and attain the Doctor of Philosophy in Medical Science. In 1942, he obtained his medical degree from Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, started a one-year residency at Johns Hopkins, and married Joy Hume, a happy union, which later resulted in four children: Gail, Ted, Don, and Beth. From 1943 to 1946, he served in the U. S. Army, Medical Corps. In November of 1948, he accepted the position of Area Medical Administrator for the United Mine Works Welfare and Retirement Fund in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, a position he would hold until 1967. But, while holding the position, he was also very active in the civil rights movement. In 1963, he was a member of the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR), which served the medical needs of civil rights and other activists during the sixties, and for a short time, he served as the MCHR's first field secretary in Mississippi. His daughter, Gail, also participated in Mississippi Freedom Summer 1964. After Freedom Summer 1964, he returned to his Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, position, where he formed a MCHR Pittsburgh chapter and attended national MCHR meetings. On October 1, 1967, he accepted a faculty position with the Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. While at Meharry he served as an officer in the MCHR Meharry chapter, and as President of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1986, his wife, Joy, died of cancer. In 1987, he retired from Meharry, moved to Vermont, and energetically devoted more time to researching and writing about the Underground Railroad, African American heroes, and African Americans who pioneered in the field of medicine. -- Falk (Leslie A.) African American History Research Collection, 1842-1999, University of Southern MississippiThe purpose of this article [in part based on presentations in July and November 1964] is to convey some insight into the Negro American's health problems -- and a few efforts by health professionals to assist in their solution. The Negro in the United States is the victim of a deep-seated discrimination-poverty syndrome. The south typifies the problems of poverty, discrimination, and segregation most clearly. But, both the north and south have had a 'closed society'. And the northern city's segregated ghetto seethes with unrest, just as does the more rural south. Both regions illustrate in different ways the unwillingness of the Negro American to continue to accept his persecution. The Negro has embarked on a heightened course of social struggle in which he has been joined by many white allies. He has now struggled to his knees and is forcing a social revolution. The civil rights movement represents perhaps the most active social just cause the United States has seen since the abolition of slavery a hundred years ago. Among the allies are many health professionals, some of them constituted as the Medical Committee for Human Rights... -- The Negro American's Health and the Medical Committee for Human Rights; Leslie A. Falk, Member, Executive Committee, MCHR, Medical Care, Vol.4, No.3 (Jul-Sep,1966), pp. 171-177Kay Fitts, a student at the University of Pittsburgh, learned of Dr. Leslie Falk's Medical Committee for Human Rights and went to Louisiana and Alabama to work on health issues -- The Civil Rights Movement in Pittsburgh: To Make This City "Some Place Special," Laurence Glasco, p.7 |

||||||||

|

Dickie Flowers

These two excerpts perhaps catch -- better than any others I've seen -- the quintessential internal contradiction in the whole noble effort. It shows up (and is commented on) in my Fall 1964 letter, and in the orientation (June-July) letters from Summer 1965:

There were certain things that occurred in the Mississippi Summer Project. One of the things we decided to do was we said that every project director in Mississippi had to be black. And every summer volunteer who was interviewed had to answer the question, "Would you be willing to go to Mississippi and serve under a project director who was black?" And interviewers were instructed to pay very careful attention to that question, because that would determine perhaps more than anything else whether you should accept this person to work in the Summer Project in 1964. And every summer volunteer was asked that question. There were certainly issues about initiative -- I remember Dickie Flowers in particular. I said, "What's the problem, Dickie?" He said, "I am the project director; I'm black. And one of the things that has happened is that a lot of the volunteers have come in and I have found myself saying I went to Morehouse when I know I didn't go to Morehouse." And I said, "That problem can be resolved. That problem occurs in every situation." There were other people who may have felt that their initiative was stifled. In any situation there are going to be some excesses, some casualties, but we have to look at the overall good... -- James Foreman, in Circle of Trust: Remembering SNCC; Cheryl Lynn Greenberg, ed., p.79 (Google book excerpt)But the many moments of racial transformation could not overcome the building tensions between the Mississippi-based COFO staff and the northern volunteers. It was these tensions -- not the interracial cooperation between local families and volunteers -- that had the greatest impact on the subsequent evolution of SNCC. COFO staffers -- mostly native to the state -- had to adjust to the fact that the tone, pace, and intimacy of the movement was no longer in their hands. The brilliance and talent of a Charles McLaurin or a Emma Bell refined in the fire of movement actions often remained unrecognized and thus disrespected by the students, who came from some of the most elite universities in the country. As James Forman remembered, black project director Dickie Flowers said that, as more northern volunteers arrived, he claimed that he attended Morehouse College "'when I know I didn't go to Morehouse.'" The highly credentialed student volunteers doubted the COFO staffers, many of whom were not college graduates, had much to offer. Worse still, it was difficult for the staff to establish new criteria for assessing "intelligence" and "skill" -- criteria that would give recognition to their own hard-won knowledge. McLaurin, Flowers, Hollis Watkins, Curtis Hayes, and others on staff grew increasingly alienated from the movement they had built. Prior to the summer of 1964, they had directed the movement's painstaking, costly nurturing of democratic self-respect, and institutions reflecting that self-respect, among black Mississippians. Northern whites, though courageous in their own right, had not experienced their sacrifices or ensuing learning processes. The black staff's internal equanimity was now at risk as they watched the local people's self-respect and institutions ebb in the face of the well-intentioned northerners. It maddened some SNCC veterans to see the confidence of native Mississippians recede in the presence of formally well-educated but culturally innocent volunteers. Furthermore, virtually none of this reality was transmitted to the larger public at the time. It was a reality that violated the sacred myths that comforted white America. It was a reality that required a respect for the democratic idea that most people simply did not yet possess. When the summer was over, COFO staffers knew, they would have to pick up the pieces. In certain ways, the entire scene constituted a mountain of contradiction with every nuance heightened by the constant violence that assaulted daily life. -- Many Minds, One Heart: SNCC's Dream for a New America, Wesley Hogan, p.45 (Google book excerpt)After Mississippi, Dickie apparently went on to other actions: [SNCC's] support increased in the fall after the NFWA joined AWOC in the first grape strikes. CORE also provided individuals and training in the strikes of 1965. But CORE's assistance quickly declined as it tackled new projects and witnessed substantial organizational upheaval, including longtime director James Farmer's departure, the move of its national office to Durham, North Carolina, and a reorientation toward black nationalism. These all made the farm workers' cause less relevant to CORE's central mission of empowering African Americans. In contrast, SNCC support of NFWA strikes and boycotts increased steadily into early 1966. The backing of both organizations was misleading, however, at least in its reflection of black-brown coalition building. With the exception of African American activists Hardy Frye and Dickie Flowers, white's facilitated SNCC's partnership with the NFWA. -- Power to the Poor: Black-Brown Coalition and the Fight for Economic Justice, Gordon K. Mantler, p.45 (Google book excerpt)As with so many young people, Chavez persuaded Ganz to change his plans for the fall and instead appeal to SNCC leaders to make him a paid representative for the student organization within UFW. SNCC responded by approving Ganz's proposal and sent him and an additional representative, Dickie Flowers -- or Dickie Flores, as the Spanish speakers in the union referred to him -- to California. -- From the Jaws of Victory: The Triumph and Tragedy of Cesar Chavez and the Farm Worker Movement, Matthew Garcia, p.54 (Google book excerpt) |

||||||||

|

Ira Grupper (picture: see Rev. Bill McAtee)

In October of 2012 I was corresponding about my Mississippi experiences with a woman who was writing a children's book about the Freedom Summer when I got the urge to find out what happened to Curt Styles. I didn't find much on the Internet, but what was there seemed to have been provided by someone named Ira Grupper. One of these sources provided an email address, and we exchanged email. Somehow, I lost touch with him, and lost track of the piece on Curt that he sent, until Rev. Bill McAtee recently sent me a copy. When my 1965 letters surfaced this year, I renewed the search for Curt, came upon the references on the web from Bill McAtee's book, and realized that Ira was a white northern volunteer who had been working in Alabama, and had come to Hattiesburg where he was recruited by Curt to work in Columbia, probably shortly after Sam and Ann and Sara and I had left. Though I neither worked with nor have met him, I include him here because he worked very closely with Curt, provided valuable information to Bill McAtee for his book, and because he has stayed true to the values that induced him, whether aware of it or not, to go South. (Note: a few bits of his history in the FORsooth piece below and in Bill's book seem to diverge in timing from my experience.) Not long after Ira Grupper left Columbia in the fall of 1966, he ended up in Louisville, Kentucky, working with Carl and Anne Braden on the staff of the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF). Ira's was among the first group of disabled person in the United States to win an employment discrimination case under the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the predecessor to the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). He worked for twenty-four years on the assembly line of a cigarette processing plant in Louisville, where he was involved as union shop steward, leader of a union rank-and-file caucus, and union delegate to the Greater Louisville Central Labor Council. Grupper's activism for social justice was not limited to the unions [many activities enumerated]. His interest was not just domestic, but international... Jerusalem... the West Bank, the Gaza Strip,... Jordan... Vietnam... Egypt. He currently writes a monthly column, Labor Paeans, for FORsooth, the newspaper of the Louisville, Kentucky, chapter of FOR, the Fellowship of Reconciliation. As an adjunct faculty member at Bellarmine University in Louisville, Kentucky, he teachers courses on the civil rights movement and Israeli-Palestinian Issues. Grupper summed up what his life's experiences have meant to him when he wrote: "The Civil Rights Movement enabled me to meet, and learn from some of the most dedicated freedom fighters, helped me understand the nature of racism, its relation to class oppression, and the international aspects of capital accumulation. It provided purpose to life, the building of the 'beloved community.' For this I will always be grateful." -- Transformed: A White Mississippi Pastor's Journey Into Civil Rights and Beyond, Rev. William G. McAtee, p.265 There's an interesting recent interview with Ira about his later activities (PDF: 38-page original, 20-page compact. For a picture of Ira, see the entry for Bill McAtee) |

||||||||

|

John Handy

AUG. 24: This excerpt from Harvard Crimson, perhaps mentioning the same event, is mostly about one of their students, William Hodes, only marginally touching on Handy -- the project director, for Pete's sake! -- but it gives a more detailed flavor of Greenwood in August 1964. Hodes and several other civil rights workers were distributing registration formed in the main Negro marketplace in Greenwood. The square is at the edge of the white district, and a crowd of whites formed across the street to jeer. When the crowd started to disperse, and Hodes started back toward the SNCC headquarters in the Negro section, a police car pulled up and five officers emerged. They accused Hodes of creating the disturbance and warned him not to do it again. At this point, Hodes said, a white store owner rushed out on the street, pointed at him and began yelling that he was "an agitator." The police then arrested Hodes, though they did not tell him what the charge was. Several of them hit him in the ribs with their billy clubs, and one police officer stabbed Hodes in the leg with his own SNCC button, the Harvard junior reported last night; "you know," Hodes said, "kid stuff." Hodes said that similar incidents have been occurring in Greenwood quite regularly. John Handy, a local Negro, was arrested the same day and beaten more severely than Hodes. He was also released on bond. A female COFO worker was arrested Sunday on a charge of assault and battery with a deadly weapon. Four hours later the charge was dropped. Tension is mounting in the Mississippi community, Hodes said, particularly as the local Negro youths are anxious to engage in direct forms of protest. SNCC officials are trying to channel their energies into the voter registration program. The local police and "rednecks" are also beginning to respond to the various SNCC programs. Hodes said. He described the community as "as tense as a compressed spring. There will probably be some more shooting during the night." And another source with local flavor is Sara Criss's "Long Hot Summer" civil rights memoir. Here's item #57, again referring to this incident: "The theater was not the only target during the 'long hot summer.' Small grocery stores operated by whites in the Negro section were also targeted, but this time it was the blacks trying to close them up. In August [1964] a crowd of 300 gathered one night at a grocery store on Avenue I operated by police officer A.E.'Slim' Henderson. Two were arrested for using profanity. Two other Negroes and white summer project workers were arrested for disturbing the peace in the Saturday night episode in front of the store. One was a 20-year-old Harvard student. "The Commonwealth stated that this incident was the 'most serious that has occurred this year. The situation was so tense police closed all places selling liquor in the city and county and ordered them to stay closed. The sheriff's department, auxiliary police, and several units of the Mississippi Highway Patrol were called to the police station to stand by in case they were needed.' "We were in the police station when those arrested were brought in. One, John Handy, a light-colored Negro who had been involved in other incidents during the summer, was standing in the station when Curtis Underwood, one of the policemen, lost his temper and gave him a heavy blow right in his stomach. That was the night [City Prosecuting Attorney] Gray [Evans] set bond at $200 and Hardy Lott [City Attorney] came down to the station and raised it to $500. "On another night three Negroes and a white man were arrested by police after a crowd gathered for the second consecutive night in front of a grocery store operated by a white woman in the Negro section. Tommie Lee Galloway, Jake McGhee and John Handy, all Negroes, and Michael Arenson, one of the summer project workers, were charged with disturbing the peace. Police officers said there were bottles and bricks thrown by the crowd and and that some windows were broken. Police officers and auxiliary police were on duty two nights to prevent further trouble. The grocery store was one of several which had been harassed by COFO workers during the summer when they attempted to prevent customers from entering the business." |

||||||||

|

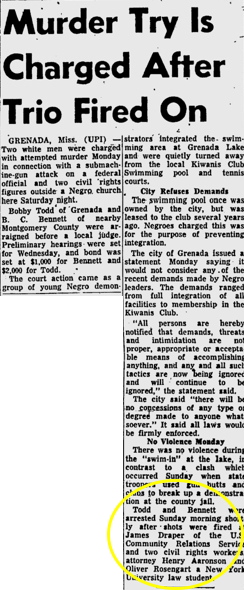

Arthur Lee (Jake) Jacobs

I could only find one reference to Jake Jacobs on the web:

|

||||||||

|

Police Chief E.E. Johnson

Five days after Dorothy Weary integrated the pubic school system in Columbia, the FDB began the boycott of Lampton's that led to the arrest of Styles, McClenton, and Grupper. It was an experience that was forever ingrained in Grupper's mind, especially because of his ensuing arrest and incarceration... After they were booked anbd frisked, the most significant part of his stay happened. Ira was put in a "white" cell by himself. Curtis and W.J. were placed in a "negro" cell next to him, but there was little, if any, difference between the two grimy cells. Ira made no bones about the fact that he was scared. Soon after the group was locked up, they started to sing along with their compatriots, who had gathered outside the jail. The chief soon put a stop to that... Later that evening, Chief Johnson came into the cell where Ira was sitting on his bunk bed. The chief was acting strangely. He said, "Boy, you ain't singing so much now," and turned his body so that his pistol was almost in Ira's face, a move that Ira interpreted as life threatening. He was now petrified and did not move a shadow. Ira glanced to the side of the chief and saw the deputy standing outside the open cell door with his hand on his holster. He then suspected that this was some sort of set-up. When Ira did not respond they left. After what he had learned from me about what Buddy had been trying to accomplish as mayor, Ira understood that probably what happened to him in the jail cell with the police chief and deputy took place in secret. He was still furious that there had been no right to habeas corpus... -- Transformed: A White Mississippi Pastor's Journey Into Civil Rights and Beyond, Rev. William G. McAtee, p.208 (Google book excerpt) |

||||||||

|

Hon. Livingstone Johnson

Judge Livingstone M. Johnson receives Amram Award "The individual chosen for this year's honor has achieved in every bar service, Bench-Bar service, and life service," said Donald Minahan, 2004 recipient of the Philip Werner Amram Award, while presenting the 2007 award to Hon. Livingstone M. Johnson during the Friday afternoon luncheon at the 45th Annual Bench-Bar Conference... said Johnson, "A lawyer's greatest mission is to work with one's colleagues at the bar and on the bench, to preserve the Constitution of these United States of America, all the while maintaining the ethics, civility, professionalism and legal excellence the practice of law demands. Being named as this year's awardee validates the many sacrifices, triumphs, disappointments, reversals, dedication, and hard work I've been required to experience in a lifetime career that I love." Johnson served as chief negotiator with the United Negro Protest Committee during the protest seeking fair employment opportunities for minorities at Duquesne Light Company. As a result of the efforts at Duquesne Light, conditions changed to the point where an African American has served as president of the company. During this same time, Johnson served as a member of the NAACP, a member of the board of the Urban League of Pittsburgh, and President of the Pittsburgh Friends of the Council of Federated Organizations...Johnson was also the first African American to serve on the Allegheny County Bar Association Board of Governors... -- Journal of the Allegheny County Bar Association, July 3, 2008, pp.1,8 |

||||||||

|

Robert R. Lavelle

Obituary: Robert R. Lavelle / Founder of Hill District's Dwelling House Savings & Loan / Oct. 4, 1915 - July 4, 2010 As founder of the former Dwelling House Savings & Loan, Robert R. Lavelle was as much preacher as banker in his evangelistic crusade to increase homeownership among the low-income residents of Pittsburgh who had trouble getting loans from mainstream banks... A handsome man even in his advanced age, Mr. Lavelle was charming, dignified and distinguished by his erect posture and the subtle radiation of his words, deeds and his commitment to serving the underprivileged. When armed robbers came into his bank and demanded money, Mr. Lavelle often tried to talk them out of committing the thefts. He never considered moving out of the Hill District, would not allow protective barriers between bank tellers and customers, and was vehemently against installing iron bars on the bank's windows and doors... A lifelong Republican, Mr. Lavelle was unabashedly conservative in his political views, but he changed his voter registration so he could vote for Barack Obama in the 2008 presidential primary. "Bob was one of my heroes in Pittsburgh. I had a lot of love for him," said Tim Stevens, chairman of the Black Political Empowerment Project. Mr. Stevens said Mr. Lavelle was the one who called him in 1969 to announce he had been selected as the Pittsburgh NAACP executive director. -- Pittsburgh Post Gazette, July 6, 2010Robert Lavelle's real estate business and Dwelling House Savings and Loan Association helped increase home ownership. -- The Civil Rights Movement in Pittsburgh: To Make This City "Some Place Special," Laurence Glasco, p.12 |

||||||||

|

Robert M. Lavelle (Jr.)

The Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) sent Robert M. Lavelle and Sharry Everett to Mississippi in the summer of 1964 to work on voter registration. Lavelle afterward continued the civil rights and community work of his father, Robert R. Lavelle... -- The Civil Rights Movement in Pittsburgh: To Make This City "Some Place Special," Laurence Glasco, p.7 |

||||||||

|

Dr. Gilbert Mason

This reference has a lot of interesting information on civil rights activity in Biloxi in earlier years, where Dr. Mason was apparently a leader from the start. Here are just a few tidbits: The Harrison County Civic Action Committee was organized in June 1959 by Drs. [Felix] Dunn [of Gulfport] and [Gilbert] Mason [of Biloxi] and Dr. Dunn was elected chairman. The two Drs. then focused on the Head Start program in the late 1960s, and the name eventually changed to the Gulf Coast Community Action Agency... The first Gulf Coast chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded by Dr. Gilbert Mason... However, many African-Americans in Biloxi and the surrounding area were wary of joining the NAACP because of the possible repercussions from the white community. As a result, initial membership and participation were better in the Biloxi Civic League and the Harrison County Civic Action Committee than in the NAACP... Many people bravely faced opposition in pursuit of better lives for African American citizens on the Mississippi Gulf Coast. One of these brave people was Dr. Gilbert Mason. Mason was born on October 7, 1928, in Jackson, Mississippi. His father, a barber, was well-respected in the community and greatly influenced Mason. While growing up he was very involved in the Boy Scouts and his local church; both strongly influenced his life. Dr. Mason attended Lanier High School in Jackson and Tennessee State in Nashville. He attended medical school at Howard University in Washington, D.C. After an internship in St. Louis, Missouri, he and his wife, Natalie, and their son, Gilbert, moved to Biloxi, Mississippi, where Dr. Mason opened his medical practice in July 1955. Mason was a civil rights leader in Biloxi and the Mississippi Gulf Coast. He led the wade-ins and lawsuits that eventually desegregated the Mississippi beach and public schools in Biloxi. He also worked for voter registration and helped organize a boycott aimed at gaining fair hiring practices for blacks at local businesses. He founded and served as president of the Biloxi branch of the NAACP. He also served as vice-president of the Mississippi NAACP for thirty-three years... Knox Walker was a white man who was Gilbert Mason's attorney and friend throughout his civil rights struggles. According to Mason: "A man like Knox Walker with fortitude, courage, and devotion to the principle of equal justice for all did not deserve to be smeared by police agencies.... Knox Walker also received some overt threats aimed at discouraging his association with me."... On April 24, 1960, a terrible race riot occurred when 40-50 African-Americans attempted to swim off of the Mississippi Gulf Coast beaches in Biloxi and Gulfport. The whites-only beach became a scene of chaos as angry whites attacked the civil rights activists with sticks, chains, blackjacks, and pool cues. Four were seriously wounded in this incident. The violence continued into the night, and two white men and eight black men suffered gunshot wounds. On April 25, 1960, two firebombs were thrown into the office of Dr. Gilbert Mason in response to his leadership of the wade-ins the day before that resulted in a bloody riot. One firebomb burned itself out. When the other exploded, neighbors quickly put out the flames. After the riots that occurred as a result of the wade-ins in April 1960, the black community in Biloxi boycotted several white-owned businesses instead of planning future wade-ins... On May 17, 1960, the Justice Department filed suit in the United States District Court to force equal access of the 26-mile beach of the Mississippi Gulf Coast for all races. After eight years of struggle and litigation, on August 16, 1968, Judge J.P. Coleman ruled that the Mississippi Gulf Coast beach was public property, available for use by all citizens. Coleman was the former Governor of Mississippi and Fifth Court Circuit Court of Appeals. In the spring of 1960, Dr. Gilbert and Natalie Mason petitioned the school board of the Biloxi public school system on behalf of their son, Gilbert, Jr., that Biloxi public schools be integrated. They wanted African-American children to have the choice to attend white public schools that received more state funds and, consequently, where better education was offered. Many classes like music, art, and physical education were only taught at public schools for white children. On August 31, 1964, four years after the first petition was filed with the Biloxi school board, Biloxi's public schools were integrated through freedom-of-choice desegregation. It was the first act of desegregation in Mississippi... -- Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive: A Brief History of the Civil Rights Movement on the Mississippi Gulf Coast See also: Mason, M.D., Gilbert R., and James Patterson Smith. Beaches, Blood, and Ballots: A Black Doctor's Civil Rights Struggle. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2000: This book, the first to focus on the integration of the Gulf Coast, is Dr. Gilbert R. Mason's eyewitness account of harrowing episodes that occurred there during the civil rights movement. Newly opened by court order, documents from the Mississippi Sovereignty Commission's secret files enhance this riveting memoir written by a major civil rights figure in Mississippi. He joined his friends and allies Aaron Henry and the martyred Medgar Evers to combat injustices in one of the nation's most notorious bastions of segregation... |

||||||||

|

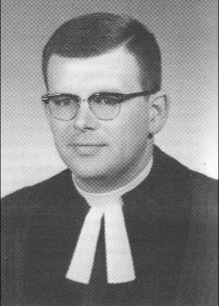

Reverend William (Bill) McAtee

Rev. Bill McAtee has played a large role in the creation of the website for this collection of letters and other materials. I had initially just wanted to get the letters up on the web, but when I did that, I realized that there was a large amount of contextual assumption in my mind that would be unknown to many others who looked at the site. So I started looking around for links to information about events, but particularly about people, and, initially, particularly about my Columbia project director, Curt Styles. The search hits on Curt seemed to come from someone named Ira Grupper, and many of the hits on him seemed to come from a book, the search-passages of which were tantalizing. I ordered the book and tracked down the author, Bill McAtee. It was wonderful talking with him, and he has provided me with a wealth of information -- much of it from the files of Mayor McLean provided by Chris Watts of the Marion County Historical Society -- about the larger context that was occurring before, during, and after the time I was in Columbia. In March 1964, Bill was a pastor in Amory, MS, and had a promise of a summer off to write his masters thesis. A seminary friend mentioned him to not-then-mayor Buddy McLean, who, as head of the Columbia Presbyterian Church pastoral search committee, recruited Bill, who set as a condition that he have that summer off. A seminary student named Dwain Epps took his position for that summer. In his subsequent role as a minister, Bill and a fellow white minister drew in four black ministers to form a group called the "Six." These men formed a vital link between the Mayor and his community (black and white) as he strove to bring them safely through the storm.

In May 1964, Bill McAtee became the new minister at Columbia Presbyterian Church, deep in the Piney Woods of south Mississippi. Soon after his arrival, three young civil rights workers were brutally murdered outside Philadelphia, Mississippi. Many other activists from across the country poured into the state to try to bring an end to segregation and to register black citizens to vote. Already deeply troubled by the resistance of so many of his fellow white southerners to any change in the racial status quo, McAtee understood that he could no longer be a passive bystander. A fourth-generation Mississippian and son of a Presbyterian minister, he joined a group of local ministers -- two white and four black -- to assist the mayor of Columbia, Earl D. "Buddy" McLean, in building community bridges and navigating the roiling social and political waters. . .

One morning in September 2002. when I was visiting Buddy's widow [Tina], we drove along Branton Avenue beside the Columbia high school on our way to a little restaurant on Broad Street to have some breakfast. The band was getting in some early morning marching practice. I had no idea how far the quality of education had progressed or about the condition of race relations. But one thing I could see when I looked at that band: I saw about as many African Americans as whites marching together in step to a lively tune. I could not help but smile. Tina turned and asked me, "Why did you come to Columbia?" I thought about it for a moment and replied, "I guess I was simply called to be Buddy's and your pastor." -- Ibid., p.229 Bill McAtee left Columbia in 1966 and spent five years on the staff of the Presbyterian Board of Christian Education in Richmond, VA, where he was "faced with very different challenges in race relations and social justice, though none as immediate and tangible as what I experienced in Columbia. In 1971, the McAtees moved to Lexington, KY, where, until his retirement in 1997 he served as first the associate executive presbyter and then executive presbyter of the Transylvania Presbyter in central and eastern Kentucky. After retiring, he "continued my life-long educational commitment to 'discovery learning,'" teaching a variety courses and workshops in a wide variety of venues, including twelve travel study seminars to Cuba. His book was published in August 2011. He is at present seventy-nine years old. (Ibid., p.266-7) I'll always wonder whether he was the white minister who communicated with us in Columbia. |

||||||||

Mayor Earl D. "Buddy" McLean

E.D. "Buddy" McLean, Jr., was born on January 23, 1925, in Gastonia, N.C... [After living in Mobile, Alabama and Fernwood, Mississippi, the McLeans finally] moved to Columbia in the mid-1930s... [He was in the Army Air Corps in WWII, went to Duke, and married wife Tina after graduation.] The McLeans were members of the Columbia Presbyterian Chruch, where Buddy served as deacon. On March 11, 1965, after "great thought and consideration," Buddy McLean formally announced his candidacy for mayor of the city of Columbia in the municipal Democratic primary to be held on May 11. "Having made Columbia my home I am deeply interested in our city, its government, and the welfare of the people," he said. He went on to declare that, "The conditions of our city, county and nation are such that we can no longer take our government for granted." He was very realistic in his estimate of the situation when he said, "I am not unaware of the fact that the next four years, as have been the past four, will be filled with problems and perhaps turmoil. No one can accurately foresee the future." His only platform was his "promise to use every ounce of my ability and the entirety of my time and efforts on our behalf" and "with your support we can grow and prosper in our city." Though this sounded like standard campaign rhetoric -- albeit without the usual Mississippi nastiness -- it was far more than that. One of Buddy's campaign strategies during these two months before the election was to knock on the door of every house in Columbia, both black and white, simply saying, "I want to be your Mayor and I ask for your vote." He accomplished this goal. He was driven to run for mayor by his vow to find ways personally to meet the challenge of the words he had used during his Kennedy memorial speech: "[H]ow utterly man [sic] has failed in learning to live together .... [We] MUST GO FORTH ... promising ourselves that we shall overcome our complacency, we shall examine our beliefs, we shall face our image, and the guilt of last Friday can never again be placed on our shoulders." It was obvious that Buddy's deep commitment caught the imagination of Six [a group of two white and four black ministers who joined forces, described on pp.97-98] and our support in his campaign... On the political scene, on April 15 A.E. "Buck" Webb announced his candidacy for the office of mayor in the municipal Democratic primary in the Columbian-Progress. Webb had lived in Columbia for about twenty years and was "proud to be a citizen." He declared his belief that "all other citizens of Columbia are interested in better government, better [everything, particularly infrastructure]... He felt his experience "will be of great value to the city of Columbia." No doubt this last would be true, especially when it came to fulfilling his campaign promise of "more and better streets." There appeared to be little if any acknowledgment of the potential problems and perhaps turmoil facing the city and county... -- Transformed: A White Mississippi Pastor's Journey Into Civil Rights and Beyond, Rev. William G. McAtee, pp.98-101 (Google book excerpt)...After his second term as mayor was over, Buddy continued as a partner in the T.C. Griffith Agency, Inc. until his retirement in 1995... Buddy died of heart failure on December 29, 2001, twenty-five days short of his seventy-seventh birthday... All these years I have carried around in my being memories of what took place in Columbia during my brief stay there in the mid-1960s. From my perspective, what happened there was unique among the experiences of southern towns at the time. Others may dispute this observation. If there were other towns in Mississippi that achieved similar accomplishments at the time, those stories should be told. If what happened in Columbia is unique, in my judgment this was due in great measure to the fact that the city had a unique person as its mayor. Buddy McLean showed great courage and imagination in the way he led the community. As we have seen, extremely powerful conflicting forces were at play, demanding an exceptional leader to meet the challenges of the day." -- Ibid., pp.228-229 |

||||||||

|

Dr. Andrew McDowd (Mac) Secrest

I had never heard of Mac Secrest until I read a reference to him in Rev. McAtee's September 2 letter. I didn't pursue him until I couldn't read his name in Mayor McLean's notes, and again stumbled on the name in the September 2 letter. He turns out to have had a tremendous influence on what happened in the South at that time.

"The Alabama State Highway Patrol, led by Commander Al Lingo, blocked passage across the Edmund Pettus Bridge spanning the Alabama River. . . . Soon the attention of the Lyndon Johnson White House and the Department of Justice was focused on Selma..." President Johnson sent Secrest and his boss, Leroy Collins, former governor of Florida and the head of CRS, down to Selma on an Air Force plane, to be greeted by a military honor guard. LBJ's purpose was to send the message that "the Feds are here, and we mean business." Secrest dined with Dr. King and his assistant, Andrew Young. They established strong rapport, and joked warmly. Knowing that Governor Wallace was a practicing Methodist, Secrest called Kenneth Goodson, Methodist bishop in Birmingham, a North Carolina native, and family friend he had known since childhood, and asked him to meet with Wallace. Goodson met Wallace in the governor's command car across the river, and prayerfully urged him to pull back his troops, let the marchers walk across the bridge, and get control of the Selma posse... |

||||||||

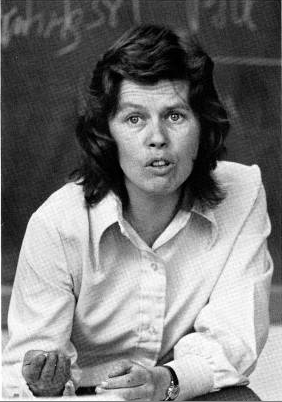

Sara Shumer

-- The Restructurations of Social and Political Theory, Richard J. Bernstein, 1978, p.ix INDIVIDUALIST, FEMINIST AUTHOR TO LECTURE HERE Dr. Sara Shumer, professor of political theory at Haverford College, Haverford, Pennsylvania, and a visiting professor at the University of California at Santa Cruz, will be a guest speaker here. Her appearance is sponsored by "The Creative Woman" quarterly and the Provost's office. Shumer is an avid individualist, so much so that she spends her summers in a cabin above the snow line in the California Sierras, (she goes up and digs out the cabin, which she built herself, every May). She will speak, appropriately enough, on "Two Concepts of Individualism," or, to put it in other words, "What the Founding Fathers Really Meant." Shumer is well qualified to speak on the subject of individualism and feminism, since she was active in the civil rights and student movements in the '60s. She has published; one of her articles appeared in the magazine, Political Theory, titled "Machiavelli: Republican Politics and its Corruption." The noted lecturer has also served as guest editor for "The Creative Woman" for their "Women in Politics" issue, Summer, '79, writing the lead article for that issue, "A Feminist Politics of Women in Politics"... -- Faze-1, August 21, 1981, p.1; Governors State University (IL) Office of Univ. Relations -- America and the Limits of the Politics of Selfishness, Sidney R. Waldman, 2007, p. ix |

||||||||

|

Curtis Styles

[See Grupper, Ira]

"I did not know Dr. [Gilbert R.] Mason, but my friend, the late Curtis Styles, was with him when the Movement integrated the beaches in Biloxi. Curt told me it was, for him, the most dangerous work he did, because when you were surrounded on 3 sides by racists, with only the Gulf of Mexico to escape to -- you could not imagine a safe way out." -- Ira Grupper, July 10, 2006 (http://www.crmvet.org/mem/masong.htm Curtis Styles, a graduate of Southern University in Louisiana and a veteran of many civil rights campaigns, entered Columbia, Mississippi, in the southern part of the state (near where he had grown up), at the end of 1963 or maybe early 1964. He had a pack on his back, and the names of a few key contacts he had written in code, in case he was accosted by the cops or the Ku Klux Klan. Curtis slept the first night in the woods. The next day he rented a house from a very courageous family [I didn't know this: the Dukes, who lived nearby on Hendrick Avenue] -- to have anything to do with civil rights workers could mean serious trouble, even death. The house was really a shack, with no indoor toilet. In the winter, the only heat was from the fireplace. We chopped our own wood. Soon this shack was transmogrified into the Freedom House, the center of civil rights activity in Marion County... Curt moved to Philadelphia PA [1966] and I to New York City and then Louisville. Curt earned a master's degree in social work, and got a job in a minimum security prison. His charges, mostly young African American first-time offenders, were motivated by Curt to learn to read or improve their reading, using Malcolm X's and other writings he gave them. Curt established a strong rapport with these boys; he was fired for not following established principles of social work. Curt vowed never to return to social work, and instead drove a truck until he retired at age 54 due to a medical condition. Curtis died, maybe six years ago, and is buried outside Philadelphia. He was 59 years old. I had the honor of saying a few words of eulogy at his funeral. -- Ira Grupper's Labor Paeans column in the March 2002 edition of the Louisville KY Fellowship of Reconciliation's newspaper, FORsooth. |

||||||||

Heather Tobis

|

||||||||

Chris Watts

|