| 7. Valley of Fear |

( Home < Issues < Mississippi letters < Mississippi Eyewitness )

Printable PDF

The Articles

|

1. Road to Mississippi 2. Mississippi Violence and Federal Power 3. Faces of Philadelphia (pictorial) 4. Interview With Dick Gregory 5. The Tip-Off 6. Mississippi Autopsy 7. Valley of Fear |

|

"make them live

in a valley of fear . . . a valley guarded by our men who will both be their only hope and the source of their fear" ADOLPH HITLER, 1939

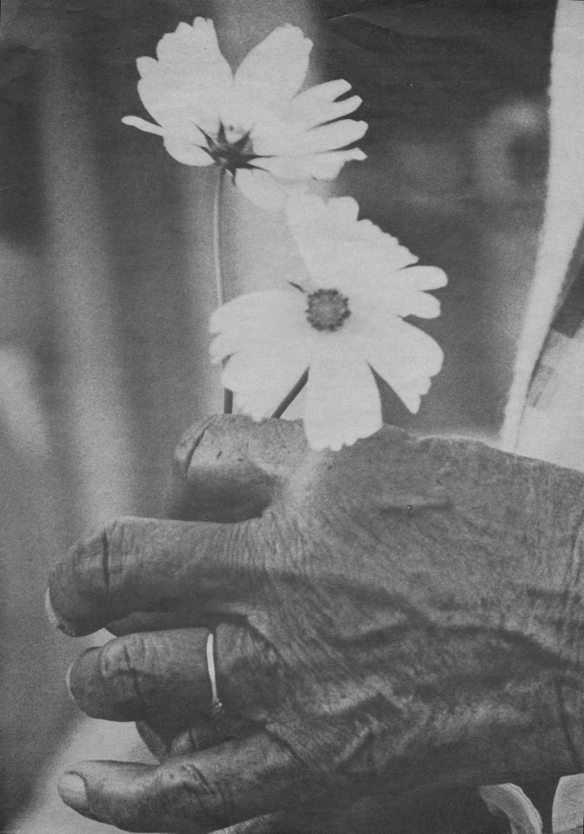

GOODMAN, SCHWERNER AND CHANEY were the 9th, 10th and 11th civil rights murders of 1964 in Mississippi. While search parties were dragging the swamps and rivers for the missing trio, fishermen turned up bodies No. 12 and No. 13, floating in the Mississippi River. Since then, at least three more Negroes have been found murdered in Mississippi, apparently with racial motive. All these killings are unsolved. Violence and intimidation of Negroes continues to be an integral part of the social fabric of Mississippi, as surely a relic of slavery as segregation or discrimination.

Violence and intimidation are openly practiced by secret societies, and encouraged in varying degrees by agencies of the state government. To treat them as a criminal aberration, or as the work of a few fanatics, is to ignore a fact of Mississippi life today. The body of a 14-year-old Negro boy who liked to wear a CORE-lettered tee shirt was fished from the Big Black River near Canton, Miss., on Sept. 10. Authorities called it accidental drowning, but a number of circumstances cast doubt on the official version. Five days earlier -- the same day Herbert Oarsby disappeared -- a Negro youth had been observed being forced at gunpoint into a pickup truck driven by a white man. That same day, dynamite charges were set at two grocery stores patronized by Negroes in Canton, where a boycott of white, merchants in the predominantly Negro town has had a crippling effect. One of the stores was wrecked. That evening eight Canton Negroes active in civil rights were picked up by police in a downtown cafe. During the week, the mother of a Negro student who had sought to attend the white high school in Canton was threatened with eviction by the owner of the house where the family lives.

Charles Fuschens, of Monticello, Miss., had never worn a CORE tee shirt. But one Saturday night last August, as be was walking home between two companions, a carload of whites drove up and stopped. Someone poked a firearm out the car window and shot Fuschens dead. Fuschens had no apparent connection with the civil rights movement. There is no civil rights movement in Monticello, a tiny courthouse town in southwestern Mississippi. Recently, however, he bought a new house and a new car, and soon afterward lost his job. He found another job, but was quickly fired from that one as well. Friends said he had acquired a reputation as an "uppity nigger" and with it, the resentment of local whites. While 200 sailors called out by President Johnson searched the Philadelphia area for a trace of the three civil rights workers, fishermen found parts of two decomposed bodies floating in the Mississippi River some 150 miles to the southwest. They were identified as Charles Moore, 19, a Negro student at Alcorn A & M College, and his friend, Henry Dee. They had left their hometown of Meadville, Miss., together on May 25 to look for work in Louisiana. Moore had taken part in a demonstration last May to protest alleged denial of academic freedom on the all-Negro campus. Some 800 Alcorn students were expelled from school after the demonstration and were held for a while in Highway Patrol custody. Two professors who had defended the students' right to demonstrate and chastised the college president for expelling them were subsequently fired. Moore, like Fuschens, was not a movement activist. But each was fighting his own private civil rights battle -- in one case for the right to protest against second-class education in a Negro state college; in the other, for the right of a Negro to be the proud owner of a new house and a new car -- just like any white man. Moore's body was found severed at the waist, the legs bound at the ankles. Dee's was a headless torso. Only after medical examination was it possible to determine their sex or race. Initially, when their remains were pulled from the river, there was strong speculation that these were the Philadelphia lynch victims. The intense interest of the national press in these bodies was swiftly dissipated, however, when it developed that they were just Mississippi Negroes with no link to the current news fad. Mississippians of both races express doubt that these murders, or any of the others, will ever be solved. Their opinion has solid historical substance. Race murder with impunity is no recent phenomenon in the South. According to the Tuskegee Institute, approximately 5,000 Negroes have been lynched in the United States. Of these lynchings, 1,797 have been documented since 1900. Best known in recent years were the Mississippi lynchings of 15-year-old Emmett Till and 19-year-old Mack Parker, whose bodies surfaced after having been thrown in the Tallahatchie and Pearl rivers, respectively. The men tried for the killing of Till, J. W. ("Big") Milam and his brother-in-law, were acquitted in a state court. The Parker case remains unsolved, although reliable sources report that authorities know the identity of Parker's killers and have evidence against them.

June Johnson, who comes from Greenwood, Miss., knows well what happens to a Negro in Mississippi who holds his head too proudly, or who tries to exercise his responsibilities as a citizen. June was only 15 when she and five other Negro bus passengers were jailed and beaten in Winona, Miss., for sitting in the "white" side of the bus terminal. Here is her account: "The state trooper took us inside the jail," she relates. "He opened the door to the cell block and when I started to go in with the rest of them, he said, 'Not you, you black-assed nigger.' "He asked me if I was a member of the NAACP. I said yes. Then he hit me on the cheek and chin. I raised my arm to protect my face and he hit me in the stomach. "He asked, 'Who runs that thing?' I said, 'The people.' He asked, 'Who pays you?' I said, 'Nobody.' He said, 'Nigger, you're lying. You done enough already to get your neck broken.' "Then the four of them -- the sheriff, the chief of police, the state trooper and another white man threw me on the floor and stomped on me with their feet. They said, 'Get up, nigger.' I raised my head and the white man hit me on the back of the head with a club wrapped in black leather. My dress was torn off and my slip was coming off. Blood was streaming down the back of my head and my dress was all bloody. Then they threw me in the cell." June and her companions stayed in jail three days, without medical treatment, before being informed of the charges -- disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. When Lawrence Guyot, a Negro field secretary for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), inquired about them at the Winona jail, he too was put in a cell and beaten. Law officers turned him over to a band of citizens, who abducted him and beat him again. Later a Federal jury found that Winona police had violated no Federal law. The Federal judge admonished the jury, as it was retiring to deliberate, not to forget that the accused were local men whose duty it was to keep the peace in Winona, while the civil rights workers were outsiders with a reputation for sowing discord and creating racial incidents. The Winona beatings took place in 1963, a year before the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) launched its well-publicized "Freedom Summer" in Mississippi. Since then, COFO has compiled thousands of affidavits documenting similar atrocities.

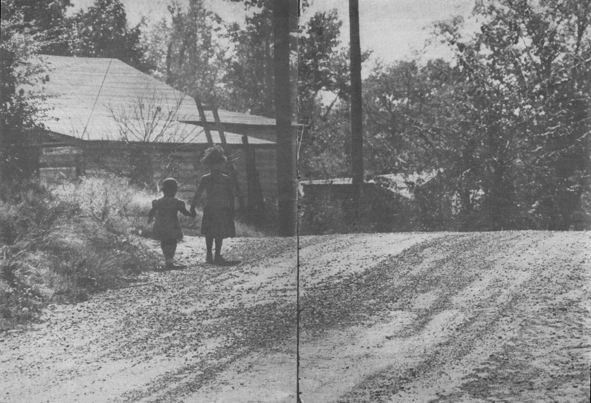

Most of it, now as before Emancipation, is anonymous terror. Who got beaten and who did the beating are facts generally not known outside the county. Only the occasional glaring atrocity receives wider attention. Since 1961, when SNCC began voter registration work in Mississippi, civil rights workers have had to share with local Negroes the fear and the reprisals. Their working unit has been the interracial team, symbolic of their determination not to succumb to their fears or be intimidated, as Negroes and whites in Mississippi have traditionally been. Peter Stoner, 25, a mild-mannered white SNCC worker, was arrested in Hattiesburg last February on charges of disturbing the peace, using profanity and resisting arrest. His sentence was a $391 fine and four months in the Forrest County Work Camp. This is his story: "The Work Camp superintendent, Les Morgan, was about to put me in a separate cell when a prisoner, Bob Moss, jumped on me and knocked me down. Morgan was standing in the door watching. I got up and Moss hit me a number of times in the face, giving me a black eye and bruises. He grabbed me around the neck and attempted to gouge at my eyes with his thumbs. After a while, Morgan stopped the assault. "On Saturdays we are allowed to make phone calls, so I called the SNCC office and told them what had happened. In the middle of the conversation, Morgan, who was listening, grabbed the phone and started hitting me. He knocked me against the door and kicked me, then locked me back up. "On April 21, Constable Kitching came to the camp to take me to Jackson, where my case had been transferred to Federal court. On the way, he attempted to get me into an argument by speaking derogatorily about the movement and Negroes in general. During the discussion, I said that I didn't think much of a person who would arrest others just to make money and that he was 'lower than many people he arrested.' Kitching became quite angry and hit me across the face with the back of his hand. "While I was in the Hinds County Jail," Stoner continued, "a number of prisoners gathered outside the door. I heard one prisoner tell others that the jailer had offered cigarettes to have me beaten up. Soon they came into the cell. A heavy, obese man named 'Tiny,' a large muscular, grey-haired man who had been in Parchman Penitentiary and another man pulled me from the bunk. "They kicked me many times in the side and kidneys, hit me with their fists all over my body, except my face as they didn't want the beating to show. The grey-haired man beat me with a wide leather strap. "After lights-out, a young prisoner attempted to have homosexual relations with me. When I resisted, he tried to beat me into submission with a belt, his feet and his fists. I fought him, although I was sick, to keep him from beating me unconscious. He finally gave up and left me alone." Last year an independent cotton farmer in the Delta led a group of Negroes to the courthouse to register to vote. A few nights later, he and his wife awoke to find their house afire. As the farmer emerged from the house with his rifle, a shot whistled overhead and thudded against the house. He spotted one white face in the bushes, then another, and fired. The arsonists, astounded that a Negro would retaliate, turned heel and ran. The man is today a leader of the movement in his county, and a hero to Negroes who have been cowed and brutalized for so long. Everyone, however, cannot be as brave as that farmer, who owns his own farm in an all-Negro area. Those who live on plantations or in rented property, or next door to a white man, those who owe the white man money or depend on him for a job, find that the risks of bravery are far too great.

Klaverns (chapters) sprang up where none had existed before, or where they had disbanded or degenerated into social clubs. A militant new leadership emerged in the klaverns, pledging allegiance to one of several rival Klan organizations, often paying little heed to the nonviolent official policy of the United Klans of America. There followed a rash of killings, beatings and threats to longtime residents of the southwestern counties during the early months of 1964. An arms depot for terrorists was reported at Natchez, with sub-bases at McComb and Liberty. Bombings of homes and stores and the burning of churches became common occurrences. A fledgling organization, the Americans for the Preservation of the White Race, came into its own, again with its main source of strength in the unreconstructed southwest, also proclaiming nonviolence in its battle to maintain segregation. Kenneth Tolliver writes about the APWR in the Greenville (Miss.) Delta Democrat-Times: "A short, fat man with graying, crewcut hair thrust a wrinkled and grimy piece of paper in front of a businessman. 'These people must be fired from your firm,' he says. 'The organization does not approve of them.' "The businessman looks at the list and notes that two of the names represent employes he has known for 20 years, but he nods sad agreement to the demands just the same.

"No, Amite County, Mississippi, 1964. "In the early days of 1963, when the APWR was coming into its own across southern Mississippi, a few men did resist. "A Liberty merchant who could trace his family back to the earliest settlers of the community, an ardent church worker and a man known for his integrity, refused a demand that he fire a longtime Negro employe. Within 24 hours a strangling boycott had been set up against his business. "The APWR stationed workers near his door who copied the names of anyone who went in. Customers, many of whom had the highest respect for the besieged businessman, turned away rather than face the intimidation which shopping in the store meant. "As the weeks went by and the merchant found himself not only on the brink of economic disaster but also effectively locked out of the town's social life, he gave in and fired the Negro." The article in the Democrat-Times, one of Mississippi's few non-racist newspapers, told of an APWR meeting at which a leading churchman was to speak. "A Liberty minister wrote to the speaker and begged him as a fellow man of God to preach love and understanding," the newspaper reported. "The speaker, with a smirk, read selections from a letter written to him by the pastor. "Needless to say, the local minister has been looking for a new church, in another city.

"PHONE CALLS THREATENING in the night are far more effective than most people believe. When a voice mentions the ease with which a child could be hurt on the way to school, the father finds it easy to knuckle down. "'The problem,' an APWR speaker told a gathering recently, 'is that we have Negroes living in this county. If they can be made to move away, we will have no further problems. Most Negro families rent their homes from white people,' he pointed out. 'All we have to do is to make white people raise rents until the Negro is forced to move away. Of course we will do it gradually, so that their loss will not affect our economy. We can start with the progressive Negroes, since they give us the most trouble,' the speaker said. "It is no nightmare that the Ku Klux Klan could burn more than 300 crosses in one night in several towns and escape without one citizen who could testify that he saw even a hooded person. The old standby, intimidation, has lowered a veil over citizens' eyes." Mississippi today is not quite Germany of 1939. It is still part of a Federal union which is pledged to enforce the Constitution everywhere within its borders. The Federal government forgot its pledge to protect the rights of newly-freed slaves in 1876, when the Hayes-Tilden compromise effectively returned control of the South to the white supremacists. Our government has difficulty remembering. The authors of Reconstruction legislation recognized that they faced two related forms of resistance in the South. The first was the use of brute and indiscriminate force by private white citizens and clandestine groups to ensure that Negroes were permanently intimidated from asserting their rights. The second challenge came from the leading officials of the white community -- government officials, law enforcement officers and members of the judiciary. By their refusal to indict and prosecute those who committed acts of violence and by their failure to enforce the Reconstruction civil rights codes, these officials became accomplices in a conspiracy to "keep the Negro in his place." Both private and highly organized forms of violence were among the tools of this conspiracy. The two forms of resistance to Negro rights operate in substantially the same way today as they did in 1866. The Klan, prime mover in the violent suppression of Negro rights after the Civil War, is back in business. It continues to draw its main support from people in the lower middle stratum of white society who seek to maintain their precarious position "above the Negro." Its leaders are small shopkeepers, used car or parts dealers, bootleggers, fundamentalist preachers. The Americans for the Preservation of the White Race displays itself as a poor man's Citizens' Council, and seeks to combine a veneer of "respectability" with the activist esprit of a mass movement. Its techniques and membership, however, more closely resemble those of the Klan. In contrast to the clandestine groups, the Citizens' Councils fall into the second type of white resistance. Their membership is solid middle class, so solid that in a typical Mississippi town, Citizens' Council members hold the balance of economic and political power in the community. Without their complicity, acts of violence could not continue unpunished. The councils work as locally autonomous units and as a state association to penetrate and control business, finance and industry, political office and the judiciary. Once in controlling positions, their members can thwart the assertion of Negro rights and are in a position to offer protection to those whites who commit violence against Negroes. Thus in Mississippi it is no contradiction for former Gov. Ross Barnett, a council member, to make a courtroom display of friendship with fellow council member Byron de la Beckwith, during Beckwith's trial for the murder of NAACP leader Medgar Evers.

When Sheriff Rainey and Deputy Price, of Neshoba County, were named as defendants in a civil rights suit filed by COFO, a Citizens' Council lawyer stood beside the assistant state attorney general in their defense. The Citizens' Councils were formed in the Delta after the Supreme Court's "Black Monday" decision in 1954, and have since spread throughout the state and nation. They are still strongest in the Delta, where Negroes form the vast majority of the population. Rarely has the economic basis of white supremacy been so clearly delineated. Negroes in the Delta chop cotton for $2.50 or $3 a day, and their children spend school vacations working beside them in the fields. The banker, lawyer, plantation owner, power company official -- who sees his interests threatened if Negroes are allowed to vote, who sees wages going up and profits going down if Negroes are allowed to organize -- recognizes his stake in breaking the Negroes' stride toward freedom. Accordingly, he may join the Citizens' Council and, with the help of his fellow members, see to it that "progressive" Negroes are fired from their jobs, deprived of welfare benefits, evicted, charged with crimes and convicted. Other Negroes are kept poor, as little educated as possible, dependent on the white employer, and sometimes in a state of virtual peonage.

The public statements of Citizens' Councils renouncing violence as a tactic, and their attempt to dissociate themselves from the indiscriminate terror of Klan-like groups, have a false ring about them. The councils have circulated lists of automobiles operated by civil rights groups -- an open invitation to terror. The license number and description of the station wagon James Chaney drove on his fateful trip to Neshoba County were on such a list. It is rumored that the tactic of selective political assassination in hopes of stopping the civil rights movement has been used by racists. Whether racist leadership formally ordered the sniper killing of Medgar Evers, and the apparent attempt on the life of COFO program director Robert Moses in which SNCC worker James Travis was seriously wounded, is open to question. That key members of this council were involved, however, is an open secret in the Delta. Unlike the Delta, dominated by an entrenched cotton aristocracy, the rural areas to the east and south are composed primarily of small farming units, and here the Citizens' Councils wield considerably less influence. "The law" in these areas is often the private preserve of the Klan-like groups.

"You live in this county?" was the rhetorical question. "Well, we live here and we don't want you in here. You better leave, and quick." It sounded like something out of a bad western, and the newsmen were incredulous and amused. Two hours earlier, an interracial group of lawyers who had come to Neshoba to investigate the burning of the Mt. Zion Church the previous week, were shoved, threatened, insulted by a crowd of whites on the courthouse steps, and again inside the sheriff's office. They were not amused. This reporter, investigating the disappearance of the three workers, was beaten within a block of the Neshoba County courthouse by four citizens of Philadelphia. At the same time, a beefy man jumped from a doorway and planted a link chain on the head of Daniel Pearlman, a law student from Connecticut. It was 2 o'clock that hot July afternoon, and people stood in the shade across the street and watched. Several months later, photographer Clifford Vaughs tried to take a snapshot of Sheriff Rainey and got two cameras smashed for his trouble. Hamid Kiselbasch, visiting professor from Pakistan at Tougaloo College, near Jackson, was returning to the campus with some academic friends last May when his car was forced off the road near Canton and surrounded by several carloads of whites. Kiselbasch was thrice clubbed on the head with a baseball bat, while one of the assailants drawled, "Let's have a party. Why don't we take them out and make an example of these nigger-lovers." The Tougaloo party had just come from a meeting in a Negro church at Canton and seen a group of club-carrying whites chatting amiably with police officers. "When these things happen," Kiselbasch said later, "and law authorities take no action, it leaves the individual practically helpless. Last night I came to realize at first-hand what I had often heard before -- that there are individuals here who are capable of carrying out their threats, and that their intentions are dangerous, and somehow subhuman. "But the most dangerous thing," be added, "is that there appears to be no recourse to law." There are hopeful signs of change in Mississippi, signs that the Citizens' Councils are losing influence, that the Highway Patrol is beginning to purge its ranks of Klan members, that state law enforcement agencies are starting to move against the house-bombers and the church-burners. A Committee of Concern was formed recently to restore churches burned by terrorists, an indication that white moderates are beginning to break through the walls of their own fear and take a stand against the race criminals. Mrs. Hazel Brannon Smith, the courageous Lexington, Miss., newspaper editor who has taken strong, editorial exception to Mississippi's organized violence, says: "I know personally that the good people in Mississippi do prevail, in the great majority. If I had not had that feeling, I just could not have gone on in the face of physical danger, economic boycott and social ostracism." Undoubtedly Mrs. Smith is right. But the terror continues, unpunished with but few exceptions, and the good white Mississippians continue silent. "Hopeful signs," eagerly sought out and played up by the newspapers, must not become wishful thinking. The lynchings of Philadelphia have been widely deplored -- by the press, by the politicians, by good folks in living rooms all over America. These murders, we are told, have "aroused the conscience of a nation"; no longer will the nation sit idly by and allow innocents to be terrorized by the virulent know-nothingism of white Mississippi. They tell us how "deeply committed" is the Federal government to enforcing civil rights in Mississippi, how effective a deterrent is the FBI presence, or how moderates are at last getting a hearing in the councils of government. It was a bad situation, we are assured, but now everything is under control. They still lynch with impunity in Mississippi. They still beat and bomb and burn, with roughly the same frequency as before the deaths of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner. What does it take to get America to care?

"make them live

in a valley of fear . . . a valley guarded by our men who will both be their only hope and the source of their fear"

|

|

1. Road to Mississippi 2. Mississippi Violence and Federal Power 3. Faces of Philadelphia (pictorial) 4. Interview With Dick Gregory 5. The Tip-Off 6. Mississippi Autopsy 7. Valley of Fear |