| 1. Road to Mississippi |

( Home < Issues < Mississippi letters < Mississippi Eyewitness )

Printable PDF

The Articles

|

1. Road to Mississippi 2. Mississippi Violence and Federal Power 3. Faces of Philadelphia (pictorial) 4. Interview With Dick Gregory 5. The Tip-Off 6. Mississippi Autopsy 7. Valley of Fear |

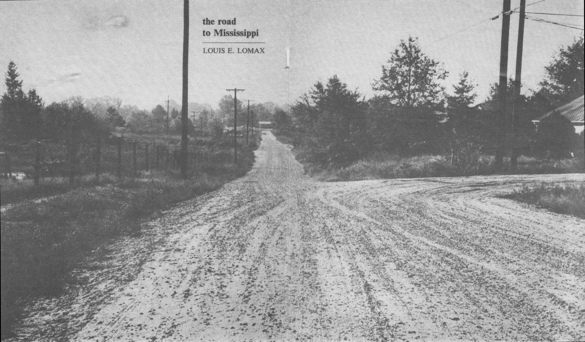

The Road to Mississippi

A DEATHLY DARK fell over the audience in Western College's Peabody Hall. The young students gathered together looked at the two Negro men on the podium, men who welcomed them to the Mississippi Summer Project and then went on to promise them that they might get killed. But Robert Moses, a serious, intent master's degree man from Harvard, and James Foreman, a college dropout who has given his all for the civil rights movement, were speaking from the depths of personal experience. And as the students talked and questioned on the rolling green Oxford, Ohio campus, Foreman and Moses never let them forget for one moment that death is always a possibility for those who venture into Mississippi as civil rights missionaries. "Don't expect them to be concerned with your constitutional rights," Moses said. "Everything they (the white power structure) do in Mississippi is unconstitutional." "Don't expect indoor plumbing," James Foreman added, "get ready to do your business in outhouses." The assemblage, mostly middle class white Protestants and Jews, roared with laughter. "Don't laugh," Moses screamed. "This is for real -- like for life and death." "This is not funny," Foreman added, "I may be killed. You may be killed. If you recognize that you may be killed -- the question of whether you will be put in jail will become very, very minute." Andrew Goodman's lip went dry. There was no longer a sophisticated "it can't happen to me" grin on his face. Like most of the other college students from across the land who had volunteered to go into Mississippi, Goodman had been motivated by a combination of conviction and adventure. Now veterans of the struggle were making it plain that Mississippi was no playground for a Jewish liberal from New York who wanted to create a better world. Then R. Jess Brown, a graying and aging Negro lawyer from Jackson, Mississippi, walked to the podium to add fuel to the volunteer's mounting fear. "I am one of the three Mississippi lawyers -- all of us Negroes --" Brown said, "who will even accept a case in behalf of a civil rights worker. Now get this in your heads and remember what I am going to say. They -- the white folk, the police, the county sheriff, the state police -- they are all waiting for you. They are looking for you. They are ready; they are armed. They know some of your names and your descriptions even now, even before you get to Mississippi. They know you are coming and they are ready. All I can do is give you some pointers on how to stay alive." "If you are riding, down the highway, say on Highway 80 near Bolton, Mississippi, and the police stop you, and arrest you, don't get out and argue with the cops and say 'I know my rights.' You may invite that club on your bead. There ain't no point in standing there trying to teach them some Constitutional Law at twelve o'clock at night. Go to jail and wait for your lawyer."

"But if you are arrested and they start beating you," Robert Moses added, "try and protect as much of your genital organs as possible." Moses knew what be was talking about. He had been arrested scores of times; he had been beaten and each time his white tormentors aimed their booted feet at the genitals. "Now," James Foreman asked, "do you still want to go?" The silence shouted "Yes". But behind the silent "amen" there were all the gnawing doubts and apprehensions that plague any man, or woman, who knowingly marches into the jaws of danger. "All I can offer is an intellectual justification for going into Mississippi," one Harvard student said. "I only want to do what I think is right to help others," a Columbia University student added. But it was Glenn Edwards, a twenty-one year old law student from the University of Chicago, who articulated what most of those involved really felt. "I'm scared," Edwards said, "a lot more scared than I was when I got here at Oxford for training. I am not afraid about a bomb going off in the house down there (in Mississippi) at night. But you can think about being kicked and kicked and kicked again. I know that I might be disfigured." Then, as the private give and take continued, the civil rights volunteers raised questions that gave the Mississippi veterans fits. "Some of us have talked about interracial dating, once we get to Mississippi," one girl told Robert Moses. "Is there any specific pattern you would have us follow?" Moses eased by the question by saying there was simply nowhere in Mississippi for an interracial couple to go. John M. Pratt, a lawyer for the National Council of Churches, one of the sponsors of the project, bluntly warned the volunteers that Mississippi was waiting for just such a thing as interracial dating. "Mississippi is looking for morals charges," Pratt warned. "What might seem a perfectly innocent thing up North might seem a lewd and obscene act in Mississippi. I mean just putting your arm around someone's shoulder in a friendly manner." But it was a tall, jet black veteran of the Mississippi struggle who rose and put the matter in precise perspective: "Let's get to the point," he said (and his name must be withheld because he is one of the vital cogs in the Mississippi freedom movement). "This mixed couple stuff just doesn't go in Mississippi. In two or three months you kids will be going, back home. I must live in Mississippi. You will be safe and sound, I've got to live there. Let's register people to vote NOW; as for interracial necking, that will come later . . . if indeed it comes at all." Those who knew him say that Andrew Goodman was among the students who gathered for the private interviews. There is no record that he asked any questions or made any comments. Some of the volunteers were frightened by what they heard and they turned back, went home or took jobs as counsellors in safe summer camps in the non-south. Andrew Goodman was not among those who turned back.

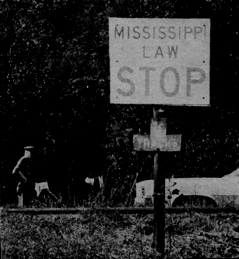

They -- the civil rights "invaders " -- were a diverse and unusual crew. Some were neat, others were beat; some were religious -- deeply so -- others were revolutionary -- even more deeply so. Many of them were first rate scholars, others were pampered football heroes on their campuses. Most of them were bright students; all of them were argumentative; most of them were unable to contain themselves until they met some backwoods Mississippi segregationist to whom they were certain they could explain the gospel on equality and constitutionalism. In all fairness to them, it must be said that their naivete was exceeded only by their energy and their courage. They really believed that white Mississippians would listen to reason if someone were willing to expend the energy necessary to spell out the ABC's of Americanism, letter by letter, syllable by syllable, word by word, sentence by sentence. Long on energy and patience, then the civil rights missionaries set out for their assignments, the God of freedom thundering in their ears, their faith in the basic goodness of all men -- including white Mississippians -- gleaming in their eyes. Like Negroes, they believed in the American Dream. It did not disturb them that once they entered the state of Mississippi, they were surrounded and followed by white policemen riding shotgun. Even as their bus curved through bayous and then raced deep into the Mississippi Delta, the civil rights volunteers amused themselves by reading dispatches from the North -- particularly a column by Joseph Alsop -- that warned of the "Coming Terrorism." Said Alsop: "A great storm is gathering -- and may break very soon indeed -- in the State of Mississippi and some other regions of the South. The southern half of Mississippi, to be specific, has been powerfully reinvaded by the Ku Klux Klan which was banished from the state many years ago. And the Klan groups have in turn merged with, or adhered to, a new and ugly organization known as the Americans for the Preservation of the White Race." Then Alsop loosed a blockbuster which should have made even the most committed civil rights zealot rise in his bus seat and take notice: "Senator James O. Eastland has managed to prevent infiltration of the northern part of the state where his influence predominates. But Southern Mississippi is now known to contain no fewer than sixty thousand armed men organized to what amounts to terrorism. Acts of terrorism against the local Negro populace are already an everyday occurrence." Then Alsop's warning became chillingly precise: "In Jackson, Mississippi, windows in the office of COFO (Council of Federated Organizations, under whose auspices the civil rights workers were coming, to Mississippi) [are] broken almost nightly. Armed Negroes are now posted at the office each night. The same is true in other Mississippi cities." The civil rights workers hit Mississippi. Two hundred and fifty graduates of the Oxford, Ohio, center alone cascaded upon Mississippi late in June. Hundreds came from other similar training schools. They went to "receiving centers" and then were assigned housing by some one hundred civil rights veterans of the Mississippi campaign, eighty of whom were from the battle-ridden Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and twenty of whom were from the Congress of Racial Equality, the most militant of the civil rights organizations. Also on hand to quiet the students were one hundred and seventy-five of their peers who had preceded them into the state and knew the ropes as well as the trees from which they could dangle. The entire Mississippi task force soon reached nine hundred -- one hundred professional civil rights workers, five hundred and fifty volunteers, all to be augmented by one hundred and fifty law students and lawyers, plus a hundred clergymen of all faiths and colors. Andrew Goodman was one of the lucky ones. Not only was be assigned to Meridian, one of the better Mississippi towns, but Michael Schwerner and James Chaney, the two Mississippi veterans who were to direct Goodman's activities, were on hand in Oxford, Ohio, to drive him back to Mississippi. By all the rules of the book, Goodman had it made. He should have served out his time in Mississippi and then returned home to New York to share with others his tale of Delta woe. But once Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner met and joined forces, the paths of their lives crossed, became entangled, then merged into a single road to tragedy.

And when the lecture was over fifty or so Queens College students gathered in a knot around me; Andrew Goodman was in the forefront. "O.K.," the students challenged me, "you have bawled us out. Now, dammit, tell us what to do? What can we do? What if we want to be committed and our parents will not let us become involved!" I don't know what I told them; I have faced the same question so often, on so many campuses across the nation, yet every time I hear it my throat goes dry. After all, how do you advise college teenagers to defy their parents and join the army of those marching into the jaws of death? My general reply is: "I have outlined the problem. Now you make up your minds where and how you can best serve in the light of your talents and gifts and temperament." Chances are that is what I said to Andrew Goodman and the other Queens College students who gathered around me. Late in the spring of 1964, Andrew Goodman made his commitment. He decided to go to Mississippi and work on the summer voter registration project. His parents wondered if he could not find involvement closer home, in a project whose moral rewards were high but whose endemic dangers were less than those of Mississippi. But Andrew Goodman was experiencing a new and deeply spiritual bar mitzvah. Andrew had entered puberty seven years earlier but now, at twenty, he had really become a man. He had decided what he wanted to live for. And since death is forever remote until it is upon us, it never occurred to Andrew Goodman that he had also decided what he was willing to die for. Those who remember Andrew Goodman during the training period at Western College in Oxford, Ohio, describe him as just another among the hundreds of civil rights volunteers. He was not "pushy"; he didn't stumble all over himself to prove how much he loved Negroes; he did not have the need to make a point of dating Negro girls. Nor was there anything dramatic about Andrew Goodman's arrival in Meridian on Saturday, June 20. Like the others, he was assigned living quarters in the Negro community and reported to the voter education center to receive work assignments from veterans Michael Schwerner and James Chaney.

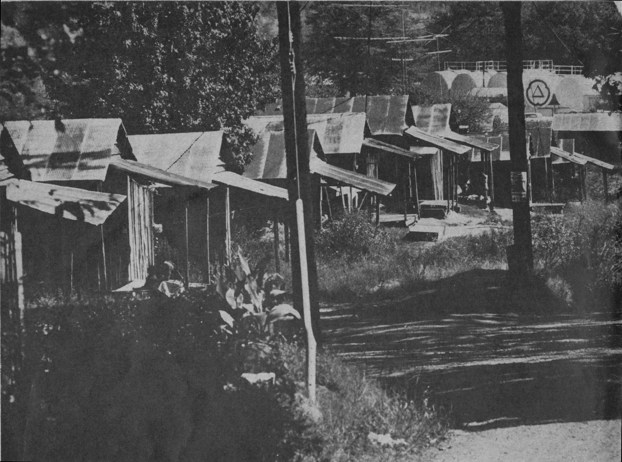

Twenty-four year old Michael Schwerner was a Colgate man. Moreover, he had gone on to take graduate work at Columbia University. Then he became a full time teacher and social worker at a settlement house along New York's ethnically troubled lower East Side. Twenty-two year old Mrs. Michael Schwerner also teaches school; New York Negroes remember her because of her way with Negro youngsters. "It was something to see," a New York social worker told me, "those little black, Negro children climbing into Rita Schwerner's lap for her to read them stories which she especially interpolated for them, in terms of their own background and experience." Michael and Rita Schwerner were staunch CORE people. They had a passion to change things; to change them now. Thus it was that the Schwerners gave up their work in New York and went to Meridian, Mississippi, last January, some five months before the summer project was to begin. They immediately set up a voter education center for Negroes and flooded the town with leaflets announcing that the center would be open each evening. Little Negro children were the first to come to the center where they and the Schwerners talked, and Michael Schwerner, aquiline nose and dark goatee, began to affect a Mississippi Negro accent. And the little children went home and told their parents of the white man with the big nose and black goatee who talked like a southern Negro. The Meridian voter education program flourished under the Schwerners. As Mississippi towns go, Meridian was a liberal community. They even had (and still have, for that matter) an unofficial bi-racial committee to keep the ethnic peace. But in the towns of Hattiesburg, Greenwood, Canton, and Ruleville, civil rights workers were facing daily beatings from white bigots and harassment from the police. "We are actually pretty lucky here" Schwerner told writer Richard Woodley early in April. "I think they (the police and the White Citizens Council) are going to let us alone. " With incredible confidence, Schwerner and his wife set up shop at 2505 1/2 Fifth Street in the blighted Negro end of town. Their five dingy rooms were the former quarters of a Negro doctor, directly over the only Negro drug store in Meridian. The Schwerners built book cases along the walls and made long blue curtains to shield the windows. The Schwerners' first effort was to infiltrate the Negro community. They found Negro boys who loved to play ping-pong and induced the Negro boys to build a ping-pong table. Then they collected typewriters, sewing machines, phonographs, office supplies, books -- such as Dollard's "Caste and Class in a Southern Town" -- which are never available to Negroes in Mississippi. The civil rights groups sponsoring the project paid the forty dollar-a-month rent on the offices and gave the Schwerners ten dollars a week for spending money. How the Schwerners lived and ate is not a matter of record. What is known is that an average of twenty people a day came to the center. Some two hundred Negroes visited the center during the first fifteen days of its operation. It took the Schwerners two months to get their telephone installed. Not only were the phones tapped, but as Michael Schwerner himself said, "If you are lucky, when you talk over our phone you can hear the police calls going back and forth." Even so, Schwerner and his wife were convinced that they were doing well. "Just look at the Mississippi Negroes we are reaching!" Schwerner exclaimed. But his wife, like all women and wives, had a deeper concern. "I must leave," she said. "If I ever got pregnant here . . . I just would never have children here. I would never go through a pregnancy or have children here." Then Michael Schwerner and his wife took writer Woodley to dinner at a Negro restaurant. "There is a job to be done here in Mississippi," Schwerner said as he fondled the crude menu in the Negro restaurant. "My wife and I think it is very important. But we want to have a normal life, and children. So eventually we will go back to New York, maybe in a year or two." They were in the Negro restaurant because there was not enough food in the Schwerner home to feed them, as writer Richard Woodley knew very well. "Darn it, Mickey," Mrs. Schwerner said, "I'm going to have a steak." Then she flailed her arms and finally pounded the table. "We need that." Michael Schwerner sat silent for a moment. Then he spoke up to Woodley. "We understand why the Negroes don't leave this state. The really poor ones wouldn't have any great life in the North even if they left. But mainly it's their home life here; they have families here and their lives are here. It is their home, and there is a little pride here that makes them not want to run." "There is no question about it," Michael Schwerner said in the middle of the meal, "The federal government will have to come into Mississippi sooner or later." The record does not show who paid for Mrs. Schwerner's steak. Chances are that writer Richard Woodley picked up the tab. Two days later Michael Schwerner welcomed Andrew Goodman to Mississippi. Schwerner told Goodman that Mississippi was no place for children. Goodman smiled and said, "I'm no child. I want to get into the thick of the fight."

"Mickey (Schwerner) and my boy were like brothers," Mrs. Chaney said. "Yes. They were like brothers. My boy a Negro and a Catholic. Michael a Jew. Yes, they were like brothers." Shortly after the Schwerners set up shop in Meridian, Chaney, who was already a member of CORE, became a full time drop out. He left school and devoted all of his time to the civil rights struggle. "Chaney was one of our best men," CORE's James Farmer said. "He was a native of Mississippi. He was a child of the soil. He knew his way around. He was invaluable." Together, then, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman made their way back from Oxford, Ohio, to Meridian. They arrived on Saturday and were immediately hit with tragic news: On the night of June 16th, while Chaney and the Schwerners were attending the training session in Ohio, the stewards of Mount Zion Methodist Church held their monthly meeting to transact church business. It was the same church in which the Schwerners had held a civil rights meeting on May 31 to rally support for a Freedom School COFO planned to open in the area. Ten persons -- officers of the church and some of their children -- attended the stewards meeting on June 16. When the church officials emerged from the church, they were confronted with a phalanx of armed white men and police officers. They started to drive away, only to be stopped at a roadblock formed by police cars and unmarked cars with the license plates removed. The police forced the Negroes to get out of their cars and submit to search. "Were there any white people at your meeting tonight?" one of the police asked. "No sir," one of the Negroes replied. "Were you niggers planning civil rights agitation?" "No sir. We were there on the Lord's business."

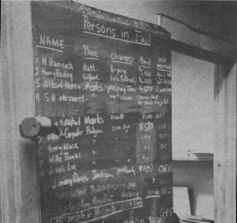

Most of all, it is the air of Mississippi that crackles with the word of God on Sunday morning. From sunrise to sunset and then to midnight, the airwaves of the Mississippi Delta are cluttered with preachers, white and Negro, the respectable and the fly-by-night, reminding the audience that Jesus will, indeed, wash them whiter than snow. And the genteel plantation owners and their families who made their way to church on Sunday morning June 21, paid no attention to the 1963, blue, Ford station wagon that eased out of Meridian shortly after 10 A.M. and headed along Route 19 toward the Route 491 cutoff. The Negro field hands, also on their way to church, paid no attention to the station wagon, either. But the police did take notice of the station wagon and they knew that two of the three occupants were Michael Schwerner and James Chaney. The police, in unmarked cars, followed closely. Switching to the "Citizens Short Wave Band" that is used to keep the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens' Council informed as to the movements of civil rights workers, the police broadcast the alarm. "They are headed north along 19. That nigger, Chaney, is driving. Over and out." Chaney and Schwerner were not afraid. They had been through it all before; Chaney had been jailed for civil rights demonstrations in Mississippi, while Schwerner had played hide-and-seek with Sheriff Rainey of Neshoba County on at least three previous occasions. In each instance Schwerner had won. This was Andrew Goodman's trial by fire; it was his first time out on a civil rights assignment. The chances are that whatever fright he felt was overshadowed by the excitement and intrigue of it all. 12:00 -- Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney arrive at the site of the burned-out church shortly before noon. They spend about an hour examining the ruins and talking with people who have gathered. 1:30 -- Schwerner, Goodman, and Chaney turn up at church services at a nearby Negro church. There they pass out leaflets urging the people to attend voter registration schools. [The name of the church and the persons who allowed the three civil rights workers to speak are known but cannot be released because of concern for the safety of the persons involved, as well as for the church building.] 2:30 -- Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney are given dinner in a friendly home and then leave for Meridian. 3:00 -- A person who knows all three civil rights workers sees them as they come along Route 16 from the Longdale area and make a right turn onto Route 491 which will take them back to Route 19 and Meridian. As soon as they swing onto Route 49 1, the three civil rights workers are intercepted by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, Schwerner's ancient and implacable foe. Schwerner is at the wheel and, as he had done on both May 19 and May 31 when he was in the area for civil rights meetings, he elects to out-run the deputy sheriff . But this time Price can act with total license. His boss, Sheriff L. A. Rainey, is at the bedside of Mrs. Rainey who is hospitalized. Four Negroes witness the chase and have later sworn that Price shot the right rear tire of the speeding station wagon. 3:45 -- The disabled station wagon is parked in front of the Veterans of Foreign Wars building on Route 16, about a mile cast of Philadelphia. Witnesses see two of the civil rights workers, now known to be Schwerner and Chaney, standing at the front of the station wagon, with the hood raised. The third civil rights worker, Goodman, is in the process of jacking 'up the right rear tire to change it. Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price (he has by now radioed the alarm) is standing nearby with his gun drawn. Informed of the incident, one Snow, a minor Deputy Sheriff, comes running out of the VFW club where he works as a bouncer. Price and Snow are then joined by State Patrolman E. R. Poe and Harry Wiggs, both of Philadelphia [The entire episode was broadcast over the shortwave citizens' band which is relayed all over the state. There is evidence that police in Meridian, Jackson, and Philadelphia, as well as Colonel T. B. Birdsong, head of the State Highway Patrol, were in constant contact about the incident. It is also clear that white racists who had purchased short-wave sets in order to receive the citizens' band broadcasts were also informed and began converging on the scene.] Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price (by his own admission) makes the arrest. (But there is confusion as to precisely where the arrest took place. Three landmarks, all within a square mile radius, are involved. Some witnesses say they saw the civil rights workers drive away from the VFW club to a Gulf station about a mile away. Others say they saw the arrest take place diagonally across the street from a Methodist Church in Philadelphia. At first blush these accounts seem contradictory. But to one who has tramped the roads and swamps of Mississippi in search of evidence -- and I have done this more times than I care to recall -- the accounts make sense.) What happened was approximately this: Price, Snow and the State Police decide that too much attention has been drawn to the incident in front of the VFW hall. They allow the civil rights workers to drive into the Gulf station location. The station wagon pulls into the gas station while the police cars park across the street. The Methodist Church in question is a hundred yards farther down the road on the other side of the street and an illiterate observer would identify the church as the landmark and say the arrest occurred across the street from the church. 4:30 -- Price arrests the civil rights workers. One of the State patrolmen drives the station wagon into Philadelphia. [This means that the tire had been changed and it accounts for the report that the wagon was at the Gulf station.] The three workers are herded into Price's car and the second State patrolman follows the Price car into town in case the workers attempt a break. They arrive at the Philadelphia jail. Chaney is charged with speeding, and Schwerner and Goodman are held on suspicion of arson. Price tells them he wants to question them about the burning of the Mount Zion Methodist Church, an incident that occurred while they -- all three of the civil rights workers -- were on the campus of Western College in Oxford, Ohio. The three civil rights workers are to report back to Meridian by four o'clock. When they do not appear their fellow workers begin phoning jails, including the one in Philadelphia, and are told that the men are not there. Meanwhile the rights workers -- charged with nothing more than a traffic violation -- are held incommunicado. What happens while these men are sweating it out in jail for some five hours can now be told. And it is in this ghostly atmosphere of empty shacks, abandoned mansions and a way of life hinged up on fond remembrances of things that never were, that the poor white trash gets likkered up on bad whiskey and become total victims of the southern mystique. The facts have been pieced together by investigators and from the boasts of the killers themselves. After all, part of the fun of killing Negroes and white civil rights people in Mississippi is to be able to gather with your friends and tell how it all happened in the full knowledge that even if you are arrested your neighbors, as jurymen, will find you "not guilty." The death site and the burial ground for Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner, and James Chaney have been chosen long before they die, months before in fact. Mississippi authorities and the white bigots have known for months that the invasion is coming. Mississippi officials have made a show of going on TV to let the nation know that they are ready and waiting with armored tanks, vicious dogs, tear gas and deputies at the ready. But there is another aspect of Mississippi's preparation for the civil rights "invaders" that they elect not to discuss: Mississippi, as Professor James W. Silver has written, is a closed society. Neshoba County is one of the more tightly closed and gagged regions of the state. Some ten thousand people have fled the county since World War II. The five thousand or so who remain are close kin, cousins, uncles, aunts, distant relatives all. For example, it is reported that Deputy Sheriff Price alone has some two hundred kin in the county. This is a land of open -- though illegal -- gambling. Indeed, the entire nation watches as a CBS reporter on TV walks into a motel and buys a fifth of whiskey, all of which, of course, is illegal. This is a land of empty houses, deserted barns, of troubled minds encased in troubled bodies. Once they receive word that the civil rights workers are coming, members of certain local racist groups begin holding sessions with doctors and undertakers. The topic of the evening: How to Kill Men Without Leaving Evidence, and: How To Dispose of Bodies So That They Will Never Be Found. Negro civil rights workers who can easily pass for white have long since moved into Mississippi and infiltrated both the Klan and the White Citizens' Council. Their reports show that doctors and undertakers use the killings of Emmett Till and Mack Parker as exhibits A and B on how not to carry out a lynching. Not only did the killers of Parker and Till leave bits of rope, and other items that could be identified, lying around, they threw the bodies in the Pearl (Parker) and Tallahatchie (Till) rivers. After a few days both bodies surfaced, much to everyone's chagrin. The two big points made at the meetings are (1) kill them (the civil rights workers) with weapons, preferably chains, that cannot be identified: (2) bury them somewhere and in such a way that their bodies will never float to the surface or be unearthed. Somewhere between ten and eleven o'clock on the night of Sunday, June 21, (if one is to believe Deputy Sheriff Price and the jailers) James Chaney is allowed to post bond and then all three civil rights workers are released from jail. According to Price the three men are last seen heading down Route 19, toward Meridian. Why was Chaney alone forced to post bail? What about Schwerner and Goodman? If they were under arrest, why were they not required also to post bail? If there were no charges against them, why were they arrested in the first place? More, if Chaney was guilty of nothing more than speeding, why had his two companions also been placed under arrest? But these are stupid questions, inquiries that only civilized men make. They conform neither to the legal nor to the moral jargon of Mississippi -- of Neshoba County particularly.

[The report that Chaney was allowed to make bail and that then all three civil rights workers were released is open to serious question. They left the jail in the evening. That is clear, but, and here is the basis for questioning the story: It is one of the cardinal rules of civil rights workers in Mississippi never to venture out at night. The most dangerous thing you can do, a saying among civil rights workers goes, is to get yourself released from jail at night. These three were trained civil rights workers and it is difficult, if not impossible, to imagine that they walked out into the night of their own volition. Nevertheless, we have the fact that they left the jail and just about three miles from Philadelphia they fell into the hands of a mob. It is not known precisely how many men were in the mob. Six, at least, have been identified by eye witnesses. But because they have not been charged with the crime, their names cannot now be revealed.] The frogs and the varmints are moaning in the bayous. By now the moon is midnight high. Chaney, the Negro of the three, is tied to a tree and beaten with chains. His bones snap and his screams pierce the still midnight air. But the screams are soon ended. There is no noise now except for the thud of chains crushing flesh -- and the crack of ribs and bones. Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner look on in horror. Then they break into tears over their black brother. "You goddam nigger lovers!" shouts one of the mob. "What do you think now?" Only God knows what Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner think. Martin Luther King and James Farmer and nonviolence are integral parts of their being. But all of the things they have been taught suddenly became foreign, of no effect. Schwerner cracks; he breaks from the men who are holding them and rushes toward the tree to aid Chaney. Michael Schwerner takes no more than 10 steps before he is subdued and falls to the ground. Then Goodman breaks and lunges toward the fallen Schwerner. He too is wrestled into submission. The three civil rights workers are loaded into a car and the five-car caravan makes its way toward the predetermined burial ground. Even the men who committed the crimes are not certain whether Chaney is dead when they take him down from the tree. But to make sure they stop about a mile from the burial place and fire three shots into him, and one shot each into the chests of Goodman and Schwerner.

Working for civil rights in Mississippi often requires underground operations. Could it be, Negroes asked, that Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney were onto something really hot, that they had arranged to vanish in order to get a major job done. Nobody, neither foe nor friend, knew the truth. In the Neshoba County area, however, strange things were beginning to occur. A Negro cook was serving dinner and heard the white head of the household say, "Not only did they arrest those white nigger-lovers, they killed them and the nigger that was with them." Then the man looked up and realized that the cook had heard him. She was fired on the spot and was rushed to her home by her white mistress who feared for the cook's life. The cook fled Mississippi that night for, as the cook well knew, her white employer was (and still is) an official in the Citizens' Council. The area is thinly populated by Choctaw Indians. There was a big Indian funeral on June 21st and they passed along both Routes 16 and 19. They saw something: the word spread that they had seen the three civil rights workers and the mob. Suddenly the Indians took to the swamps and would not talk -- even to FBI investigators. But most of all that silent meanness that only a Negro can know and feel -- the hate stare that John Howard Griffin found when he himself became black and got on a bus in the deep South -- settled over Neshoba County like a deadly dew. "Lord, child," a Negro woman told a CORE investigator, "I have never seen the white folks act so mean for no reason at all. They just don't smile at me no more. It's like they done did something mean and think I know all about it!" The white people were not too far from wrong. Somebody had did something mean and -- the whole country knew about it. They knew about it because, once murder was done, the whites involved went to a bootlegger, got themselves several gallons of moonshine and proceeded to get drunk and brag about the two white nigger-lovers and the nigger they had just finished killing. Despite what Sheriff Rainey, Governor Johnson and the two Mississippi Senators said, within twenty-four hours after the triple lynching, everybody in the county, Negro and white, knew that the civil rights workers were dead.' They also knew who committed the crimes.

Ignoring the claims that the civil rights workers were still alive, the sailors moved into Mississippi and proceeded under the assumption that the three were dead, as, of course, everybody knowledgeable about the matter knew they were. Once they had arrived in Mississippi, the sailors donned hip boots and began to comb the swamps and the bayous, hardly places one would look for men who are hiding out. Then two days later the first break came. The blue Ford station wagon in which the civil rights workers had been traveling was found charred and burned along a road some ten miles northeast of Philadelphia. The charred station wagon was discovered late in the afternoon and natives, Negro and white, who had used the road that morning, came forth to say that the wagon had not been there earlier in the day when they had passed the spot on their way to work, The truth is that the station wagon was not there on the morning of the 22nd. Rather, the killers had doused the station wagon with the same kind of naphtha that had been used to burn down the Mount Zion Methodist Church. In addition, they set it on fire several miles from the area where the station wagon was finally discovered. This fact is borne out when it is recalled that most of the foliage around the area where the charred station wagon was found was unscarred. Had the station wagon been put to the torch where it was found the foliage would have been scarred and the blaze would have attracted people from miles around. Clearly, and without a doubt, the station wagon had been burned elsewhere and had been towed to the site where it was discovered. Not only did the traces of naphtha show up, but investigators were struck by the fact that only the metal parts of the station wagon remained undestroyed. This grim discovery served to intensify the search. Only the noisy psychopathic Mississippians could continue to insist that the disappearance was a hoax, that the three civil rights workers had intentionally vanished and were hiding somewhere behind the Communist Iron Curtain, preferably in China.

Other FBI agents were conducting an investigation on land. They zeroed in on Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence Rainey who, by his own admission, had killed two Negroes in recent years. "Yep, by God," Rainey told the investigators, "I killed them two niggers. The first had me down on the ground choking me. The other nigger I killed was shooting at me." But Sheriff Rainey did not join in the hunt for the missing civil rights workers. That same day there was a flurry of excitement when the body of an unidentified white man was found in a swamp near Oakland, Mississippi, some one hundred miles from the search area. The first reports indicated that the body was that of Michael Schwerner. Instead it turned out to be that of a carnival worker who had been run over and mutilated in a highway accident. Just how that body wound up in a Mississippi swamp has yet to be explained. While the world wondered and pondered, white Mississippi sensed the truth. As osmosis is the mysterious passing of a liquid through a membrane, so is spasmodic reality the mystic, lucid, moment when white Mississippi admits the truth about itself. The moment is brief, the lucidity is blurred, but the memory remains and as white Mississippi awakes to the smell of magnolia blossoms it cannot deny that part of last night's nightmare was real. Then white Mississippians grow real mean and protective. As the search for the missing civil rights workers continued Mississippi born Frank Trippett, now an associate editor of Newsweek magazine, drove throughout his homeland to talk to the men and women, the boys and girls he played marbles with when he was a child. "John F. Kennedy should have been killed," one of Trippett's childhood chums told him. "He had no business going down to Dallas just to stir up them people and get votes." Then Trippett's one time playmate went on to wish for the future: "They proved it out in Dallas. They's always one that can get through. I tell you, little Bobby [Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy] better not come down around here." But Trippett didn't want to hear about the Kennedys. He wanted to know what his childhood friends in and around Neshoba County felt and knew about the disappearance of Michael Schwerner, James Chaney and Andrew Goodman. Nobody would talk about that. The cotton curtain had long since descended and any white man who talked about what happened to the three civil rights workers was not only a traitor to the south but an ethnic bastard to boot. Asked about the three civil rights workers, Trippett's childhood playmates lapsed into the oblique morality that earned William Faulkner a Nobel prize for literature. "There's going to be some killings if these niggers start trying to get into cafes and things," an old friend told Trippett. "Every store in Starkville has sold out every bullet they can lay their hands on." Reporter Trippett did his best but none of his childhood friends would talk about what they all knew had happened over on Route 16, near the Longdale area and just outside of Philadelphia. One of Trippett's friends, however, got dangerously close to the truth. This friend, a well educated man now in his early middle years, took Trippett home to dinner. Midway through the meal the man turned to his wife and said "would you kill one?" They and Trippett knew the man was asking his wife if she had the courage to kill a Negro, or to put it another way, would she have done what they all knew several men had done a few nights previously along Route 16? The wife blushed, then turned to reporter Trippett. "Do they give you any trouble in New York? Do you let them know you are from Mississippi?" Trippett kept his silence. "I guess you will go back and write a whole lot of lies about us," his host said. "No," Trippett replied. "I am going to do worse than that. I am going back and write the truth." Once out of Mississippi, Trippett added a footnote to the conversation. "I will not write the truth about Mississippi," he said, "only because the truth about my home state is so incredible that nobody will believe me." But, as we Negroes in Georgia used to say, the truth did out. It outed in a way no civilized person could believe or deny.

Missing in this statistical braggadocio, of course, is the fact that Mississippi simply does not list the crimes of whites against Negroes. Alas, Mississippi statistics also fail to list crimes of Negroes against Negroes, who comprise forty-five per cent of the state's population. The raw facts are these: Mississippi authorities know of at least nineteen church burnings, fifty floggings of Negroes by whites, another one hundred incidents of violence to Negroes by whites, and at least eleven Negro deaths which are almost certainly lynchings. There have been no arrests for any of these crimes and they are not among those reported as Mississippi presents its clean bill of health to the nation. Meanwhile the search for the missing rights workers continued. Negro comedian Dick Gregory flew into Mississippi and obtained an interview with a white man and said he had final evidence of what had happened on the night of June 21st. Gregory then went on to offer a twenty-five thousand dollar reward for information that would lead to the arrest and conviction of the killers. But the FBI, under the whiplash from President Johnson who was being inundated with demands that the government do something about the killings, quietly spread the word that they would pay twenty-five thousand dollars for information leading to the location of the bodies and the arrest and conviction of the lynchers. There was a brief flurry of excitement when the dismembered bodies of two Negro men were found floating in the river along the border between Mississippi and Louisiana. It turned out, however, that these were not the bodies of the missing civil rights workers and the grim search continued. The killers had learned their lessons well. There was no longer doubt that the three civil rights workers were dead and buried. Rather, the Bayou bingo game turned on whether the FBI could find bodies that had been buried in such a fashion that they would never float to the surf ace, and on whether, like the Jesus the killers professed to serve, they would ever rise again. The bodies did not float. They did not rise again. Had they remained where the killers buried them the bodies would have been unearthed, perhaps, by twenty-fifth century man as he attempted to decipher the hieroglyphics of our age, the nonsay language of a civilization whose founding documents, roughly translated, said all men are created equal: that all men, regardless of race, creed or color were free to pursue happiness, catch as catch can. Blood, in the deep south of all places, is thicker than water. But greed, particularly among poor Mississippi white trash, is thicker than blood. The Government's twenty-five thousand dollar reward was more than a knowledgeable poor white Mississippi man could bear. He cracked and told it all. The white informant knew it all and he spilled his guts all night long.

One morning FBI agents came calling on trucker Olen Burrage at his office some three miles southwest of Philadelphia. "What you'all want?" Burrage demanded. "We have a search warrant." "For this office?" "Nope" the Federal men snapped. "We have a warrant to search your farm." "Well, by God, go ahead and search it," Burrage snapped. "Look all you'all want to." The FBI agents were all set to do just that. They moved on to Burrage's farm, some two miles down the road, along Highway twenty-one. They used bulldozers to cut their way through the tangle of scrub pine, kudzu vine, and undergrowth to a dam site under construction several hundred yards from the roadway. Then they moved in the lumbering excavator cranes. The cranes began chewing away the clay earth and the recently laid concrete. While the natives, Negro and white, looked on in disbelief, the cranes gnawed out a V-shaped hole in the twenty foot high wall that shielded the dam. There, under a few feet of concrete, in the drizzly Mississippi dusk, they found the bodies of Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman and James Chaney. The fantasy was over. No. I apologize, it was not over. It had just entered another chapter. Deputy Sheriff Price was on hand and he helped lift the three bodies from the dam site and wrap them in cellophane for shipment to Jackson for further study. The remains were slithered into separate cellophane bags and tagged "X1", "X2" and "X3". In Jackson the bodies of Schwerner and Goodman were identified by fingerprints and dental records. There was no way to be certain, but the third body was black and there was little doubt that it was James Chaney. The macabre discovery told the nation what a few of us had already known, what the rest of us had feared. The three civil rights workers were quite dead: Chaney, the Negro in the trio had been brutally chain-beaten. and then shot. His white brothers in the faith had then been shot to death. The only questions that remained were: who were the killers and what would happen to them. But, and this is the irony of the matter, by then everybody -- from Moscow, Mississippi to Moscow, Russia -- knew how, where, when, and by whom the rights workers were slain.

"I just didn't think we had people like that around," said the coach of the all white Jackson, Mississippi, football team. But other white Mississippians took a different view. They were appalled that a white Mississippi stool pigeon would tell on other white Mississippians. "Somebody broke our code" one white Mississippian told the FBI. "No honorable white man would have told you what happened." But in the hearts in black Mississippians there was great rejoicing. "I am sorry the three fellows is dead," a Mississippi Negro told me. "But five of us that we know about have been killed this year and nobody raised any hell about it. This time they killed two ofays. Now two white boys is dead and all the world comes running to look and see. They never would have done this had just us been dead." Rita Schwerner, dressed in widow's weeds, was much more precise about it. "My husband did not die in vain," she told a New York audience. "If he and Andrew Goodman had been Negro the world would have taken little note of their death. After all the slaying of a Negro in Mississippi is not news. It is only because my husband and Andrew Goodman were white that the national alarm has been sounded." Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney are all now buried, asleep with their forefathers. Goodman and Schwerner lie in six feet of rest and peace, beneath the clay that covers all Jews in New York County. James Chaney rests alone, beneath the soggy clay on the colored side of the cemetery fence that separates the white who are dead and buried from the colored who are dead and buried in Mississippi. |

|

1. Road to Mississippi 2. Mississippi Violence and Federal Power 3. Faces of Philadelphia (pictorial) 4. Interview With Dick Gregory 5. The Tip-Off 6. Mississippi Autopsy 7. Valley of Fear |