Tripping over the Truth — two competing theories of cancer's origin

excerpt

from the book Tripping Over the Truth, pp. 143-147

by Travis Cristofferson, MS

(editorially added in italics: context, headings, names, annotated table, additional references)

(Updated: 6 December 2025)

(

Home <

Issues <

Health <

Cancer <

Metabolic Theory

)

Printable PDF

|

This book is the best introduction to this topic that I've encountered: https://www.amazon.com/dp/1603587292/

The Excerpt:

...While looking for the link between damaged respiration and uncontrolled growth, [Dr. Thomas] Seyfried proposed that chronic and persistent damage to the cell's ability to respire aerobically triggered an epigenetic signal from the mitochondria to nuclear DNA. The signal then altered the expression of a plethora of key cancer-causing oncogenes—a classic epigenetic system. [Dr. Bert] Vogelstein readily admitted that epigenetics may play a much larger role in cancer than expected. One problem, he said, was that "epigenetics just don't lend themselves well to experiments." Nevertheless, Seyfried illuminated the basic research showing the important epigenetic signaling that travels from the damaged mitochondria to the nucleus, the missing link to a complete metabolic theory of cancer.

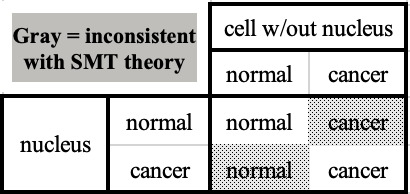

Damaged mitochondria set up the nucleus for cancer To construct a single metabolic theory of cancer, Seyfried connected the last remaining dots. He tied injured mitochondria to uncontrolled proliferation, the pathological feature of cancer that [Dr. Rudolph] Virchow had documented more than one hundred years before. Fortunately for Seyfried, the tangled relationship between the mitochondria and the nucleus was being sorted out. In addition to supplying the cell's energy needs, mitochondria were known to regulate many cellular functions, including iron metabolism, heme and steroid synthesis, programmed cell death, and cellular division and differentiation. To perform these functions, mitochondria "talk" constantly with the nucleus, relaying signals and materials back and forth. [Dr. Peter] Pedersen had shown that the single transformation of hexokinase to hexokinase II drastically alters the metabolic landscape of the cell. By binding to the mitochondrial outer membrane, it turns the cells into immortal, crazed fermenters. In 2012, when Seyfried released his book, there was substantial experimental evidence showing how damaged mitochondria send a distress signal, called "the retrograde response," to the nucleus. The signal tells the nucleus to transcribe a host of genes responsible for preparing the cell to ferment glucose in order to compensate for declining oxidative energy production. The genes that respond to the mitochondrial distress call have foreign-sounding names: MYC, TOR, RAS, NFKB, and CHOP. Collectively they have profound consequences when turned on. MYC, a protein with global operations, acts as a transcription factor. It alone controls 15 percent of the entire genome. It affects vast swaths of the genomic landscape, turning some genes on and putting others to sleep, but most significantly it begins the process of tumorigenesis. Most of the genes turned on by damaged mitochondria sit at signaling hubs and therefore dictate multiple operations such as cell division and angiogenesis (the growth of new blood vessels to supply the tumor). Seyfried contends that if the retrograde response signal is chronically "on"—as is the case when mitochondria are damaged beyond repair—trouble ensues. In addition to ramping up the proteins necessary for a massive increase in energy creation through fermentation, a persistent retrograde response would cause side effects such as uncontrolled proliferation. A sustained retrograde response has even more dire consequences. As the response becomes chronic and genomic signals transition the cell into a different cellular architecture, the legions of proteins designated to protect and repair DNA begin to stand down—drying out the moat and leaving the castle unguarded. [Dr. Cyril] Darlington noticed this phenomenon as far back as 1948 and had written, "The development of unbalanced nuclei in tumors is without precedent in any living tissue. It implies a relaxation of detailed control of the nucleus which is also without precedent. And this in turn argues that the nucleus is not itself directly responsible for what is going on." Left unprotected, the chromosomes are vulnerable to mutations by the increasing prevalence of free radicals generated by the damaged mitochondria. The timing is critical: The retrograde response comes first, then genomic instability. This single detail, the timing, is crucial, implying that the mutations thought to initiate the disease are merely a side effect. This went a long way toward explaining the mystifying data from TCGA [The Cancer Genome Atlas — a massive decades-long and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to identify key tumor-specific cancer genes], and it also explains the contradictory low mutation-high cancer rates that [Dr. Larry] Loeb had noticed. If cancer is driven by the retrograde response, this explains how mutations can vary wildly from patient to patient and how samples with one or two mutations could exist. It implied that rather than driving cancer, mutations were just features of its personality. According to Seyfried, the mutations at the heart of the SMT of cancer were downstream to the true cause: damaged mitochondria. They are a side effect, an epiphenomenon. The upshot is that mutations to DNA "arise as effects rather than as causes of tumorigenesis," Seyfried said. The mutations seen in the DNA of cancer cells are "red herrings" that had sent researchers on a futile hunt. The crucial, clinching experiments — last nail in the coffin of the SMT The most striking evidence that Seyfried dug up was from the late 1980s: a series of uncomplicated experiments that drew remarkable conclusions. Not all experiments are created equal; some are better than others. Experiments that are technically simple in design yet offer results that answer big questions tend to leave a lasting mark in their fields. Two groups working independently, one in Vermont and the other in Texas, performed a meticulous series of nuclear transfer experiments, both with shocking results. The experiments consisted of a simple transfer. Warren Schaeffer's group at the University of Vermont wondered how much control the cytoplasm (where all the mitochondria reside) had over the process of tumorigenesis. To find out they conceived of a beautiful experiment. Simply put, they took the nucleus of a cancer cell and transferred it into a healthy cell with its nucleus removed. The reconstituted cell (or recon) now contained the DNA of the cancer cell, with all its supposed driver mutations, but retained the cytoplasm and mitochondria of a noncancerous cell. The recon now had tremendous power. It alone could answer the question of who was right: [MT originator Dr. Otto] Warburg or [SMT proponents Dr. Harold] Varmus and [Dr. Michael] Bishop. If mutations to DNA caused and drove cancer, the recons should be cancerous, regardless of their healthy mitochondria. But if, as Warburg, Pedersen, and Seyfried contended, the mitochondria are responsible for starting and driving cancer and mutations were largely irrelevant, the recons should be normal, healthy cells. The Vermont group found that when they transplanted the recon cells into sixty-eight mice, only a single mouse grew a tumor over the course of an entire year. The cells containing the mutations thought to be responsible for the disease were silenced by the healthy cytoplasm (mitochondria). But without a metabolic theory of cancer in place, or any theory that explained these results, Schaeffer's group was not sure what to think. They knew that what they found contradicted the prevailing dogma, but they struggled to find an explanation that made sense. While the Vermont group mulled over the strange outcome, Jerry Shay's group at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas confirmed Schaeffer's results. They ran the same transfer experiment and injected the recons into ten mice. Not a single one developed a tumor, substantiating the amazing results seen in Vermont. Like Schaeffer's group, the Texas group struggled to make sense of the results. To ensure that an experimental artifact wasn't screwing up their finding, Shay's group per formed a set of painstaking controls. They took the nucleus of a cancer cell and transferred it into the cytoplasm of another cancer cell. They wanted to make sure that the experimental procedure itself wasn't responsible for turning the recons into normal cells. Seven out of the eight control recons remained cancerous when transferred to mice. They then reversed the control and transferred normal nuclei into normal cytoplasm. None of these recons turned cancerous in the mice, confirming that the shocking results were not due to an experimental artifact.

Schaeffer's group next ran the same experiment in reverse. Instead of adding the nucleus of a cancer cell to the cytoplasm of a normal cell, they added the nucleus of a normal cell to the cytoplasm of a tumor cell (a whole tumor cell with its nucleus removed). If mutations to DNA caused cancer, the recons should remain healthy, normal cells. However, if damage to the mitochondria, followed by a retrograde response to the nucleus, was the cause of cancer, the recons should became cancerous. Again the results flew in the face of everything known about cancer, directly contradicting the SMT of cancer. When they transplanted the recons containing a malignant cytoplasm and a normal nucleus into newborn mice, 97 percent of the mice developed tumors. The fact that both groups had demonstrated that the cytoplasm of a normal cell, with normal mitochondria, could suppress cancer was one thing, and ardent devotees to the SMT may have been able to turn the other cheek on an isolated series of experiments. But when Schaeffer's group proved irrefutably that the cytoplasm of a tumor cell on its own could initiate and drive cancer, it was impossible to ignore the results. Schaeffer claimed, "Here we present the data which, for the first time, provide unambiguous evidence indicating a role for cytoplasm in the expression of the malignant phenotype." Astonishingly, rather than shaking the very foundation of cancer biology, the claim was ignored—even worse than being argued against. The beautiful experiments were loaded with theoretical implications, and some would argue that they should have altered the trajectory of a portion of NCI money. But the NCI made the decision that the experiments, even with their astonishing connotations, merited no further exploration. If Seyfried had not dug them up, they may well have been forgotten. Seyfried reflected on the lost importance of the experiments, saying, "In summary, the origin of carcinogenesis resides with the mitochondria in the cytoplasm, not with the genome in the nucleus." How was it possible that so many in the cancer field seemed unaware of the evidence supporting this concept? How could so many ignore the findings while embracing the gene theory? Perhaps [Dr. Peyton] Rous was correct when he observed "the SMT acts like a tranquilizer on those who believe in it." The results of these carefully conducted and duplicated experiments seemed inescapable: Cancer was driven by the cytoplasm, as Warburg had claimed. Schaeifer recalls:

Schaeffer felt the experiments deserved more attention and funding, but the NIH was focused on genetics and was not about to change course...

|